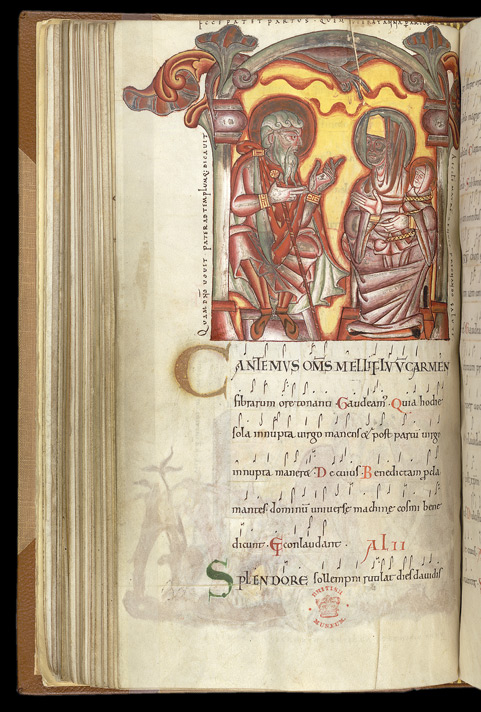

Domesday Book, 1st August 1086

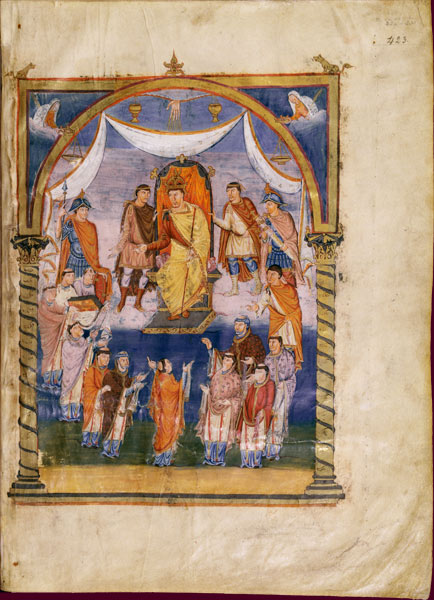

On 1st August 1086 William of Normandy called a great meeting at Old Sarum, where he had built a royal castle on the Iron Age hill fort at Salisbury. It was attended by all the men of consequence in the kingdom, not just his immediate advisers, and they swore allegiance to him. It was also the opportunity to present the first completed section of the Domesday Survey which had been commissioned the previous December.

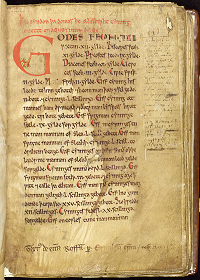

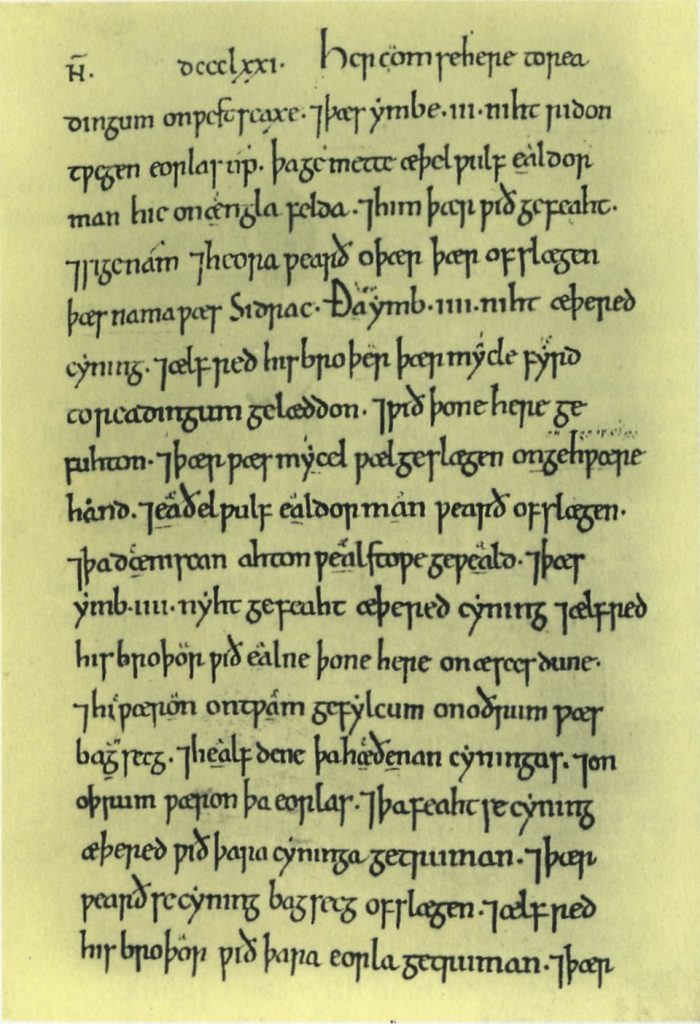

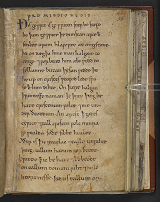

Here´s the full entry for the year in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

“AD 1086. This year the king wore his crown and held his court at Winchester, at Easter [5th April], and so he journeyed that he was at Westminster at the Pentecost [24th May], and he dubbed his son Henry as knight there. Afterwards he moved about so that by the Lammas [1st Aug.], he came to Salisbury, and there his witan came to him, and all the tenants of land that were of consequence over all England became the vassals of this man, whosoever they were, and they all submitted to him and became his men, and swore to him oaths of fidelity that they would be faithful to him against all other men.

Thence he went into Wight, because he intended to proceed into Normandy, and so he did afterwards; but before this he did according to his custom, he obtained a very large sum of money from his people where he could make any charge, either with right, or otherwise.

Then afterwards he went into Normandy, and Edgar etheling, the relative of king Eadward, then went off from him, because he had no great honour from him; but may Almighty God give him worship for the future!

And Christina, the sister of the etheling, betook herself into the minster at Romsey, and took the holy veil.

And this same year was a very heavy year, and a very laborious and a sorrowful year within England by the murrain of cattle, and corn and fruits were left standing; and such mishap was there in the weather as that one cannot easily think; such heavy thunder and lightning was there that it killed many men, and ever it grew worse among men, more and more. May God Almighty amend it, when his will is!”

This first draft of Domesday concerned Yorkshire, so is of particular interest to our Yorkshire group. If we go back in the Chronicle to the previous year we find the scope of the Survey, which certainly did not meet with the Chronicler´s approval:

“1085…After this the king had a great meeting, and a very deep conference with his witan concerning this land, how it was leased out, or to what kind of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire, and directed them to ascertain how many hundred hides were in each shire, or what quantity of land the king himself held, and how much stock was upon the land, or what dues he ought to have by the twelvemonth from the shire. Also he caused to be recorded in writing how much land his archbishops held, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbats, and his earls, and (though I take long to tell it,) what, or how much, each man, who was a tenant of land, occupied within England, in land or in stock, and how much money it was worth. So exceedingly narrowly did he cause the investigation to be made, that there was not one single hide, nor one yard of land, nay moreover—it is a disgrace to recount it, but he considered it no disgrace to do it,—neither an ox, nor a cow, nor a swine was there left, which was not written down in his record. And all these writings were brought to him afterwards.”

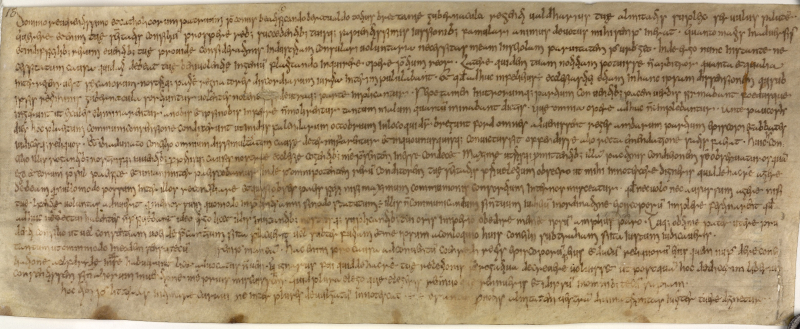

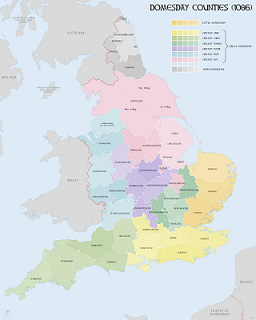

In order to conduct the Survey, the shires were grouped into seven circuits to be recorded by appointed commissioners who held no or very little land within the circuit to which they were assigned. The commissioners held sessions at the shire courts to receive reports from the royal officials in the shire, as well as from juries representing the Hundreds. In some instances local landowners also testified, but a great deal of material was submitted in written reports. This is why the Domesday record does not represent actual villages so much as estates/manors or vills (units of taxation).

The returns were then compiled for the king, arranging the king´s holdings geographically. The landholders´ estates were listed by tenure to describe a total holding to establish taxation levies. Domesday contains records for 13,418 settlements in the English counties south of the rivers Ribble and Tees (the border with Scotland at the time).

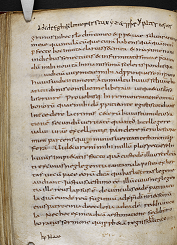

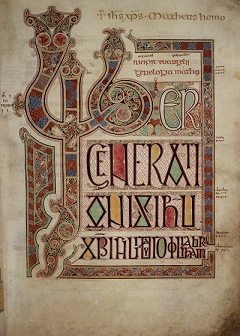

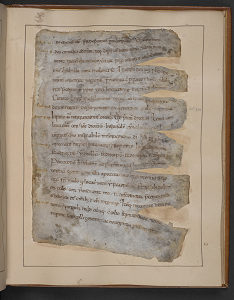

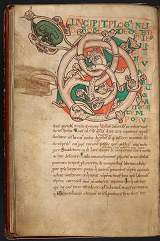

The work was completed by mainly one scribe, with some additional corrections by a second person. The original document therefore contains numerous notes and additions as the scribe attempted to impose some consistency and structure on the varied format of the material he received. The Survey was intended to be compiled into one complete volume, but was never fully completed, probably due to William’s death in September 1087. However, the information collected from the whole survey was retained in two volumes: firstly ‘Great Domesday’ which comprises 413 pages containing most of the counties, and is abridged; and ‘Little Domesday’ containing 475 pages covering the three counties missing from Great Domesday (Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk) and is unabridged. The “Yorkshire summary” is appended to Domesday and helps to convert holdings in the Danelaw from a geographical to a tenurial format, although it is not clear whether it pre-dates the Survey or was part of it.

The Domesday contents for Yorkshire indicate the ongoing effects of the Harrying of the North in 1069-70 and problems of establishing full Norman control. Although there is some debate about the meaning of the term “waste” in the text, clearly in a number of cases it refers to areas destroyed by the army. Yorkshire was not the only place with land made waste, but it was the hardest hit both in terms of land productivity and population. Lincolnshire, East Anglia and East Kent were the most densely populated areas with more than 10 people per square mile, while northern England, Dartmoor and the Welsh Marches had less than three people per square mile. However, it should be noted that “waste” areas may also refer to the failure to pay geld for various reasons.

The text shows that around 17% of the land across England was held by the king, 26% by bishops and abbots, and the remaining 54% by 190 lay landholders. Some of the holdings were spread far and wide. For example, twenty of the lords held land in 10 or more counties, and fourteen of them had lands both in the north of the country and south of the Thames. The majority of landholders were now from Normandy, with many of the former English landholders listed as sub-tenants, demonstrating the imposition of the Norman feudal structure of land-holding and the enormous restructuring of ownership.

Much of the land was used for agriculture of course, with 35% being arable, 25% being pasture/meadow, and 15% being woodland. Arable crops included wheat, barley, oats and beans. Domesday records over some 6000 mills to grind the grain. Pasture was for grazing, and the more valuable meadow bordering watercourses could be used for both grazing and hay. Sheep were of great economic importance and other animals included in the records are goats, cows, oxen and horses, wild horses and forest mares. Bees were also extremely important to produce honey and wax (and mead!). Domesday Book also records fisheries on weirs along the main rivers, but fishponds are also noted and the number of eels produced could be 1000 per pond.

Death of Alfweard, 1st or 2nd August 924

Alfweard Atheling, second son of Edward the Elder, died on 1st or 2nd August 924 AD, only a couple of weeks after his father.

It was a complex set of family relationships. Alfweard was the son of Edward and his second wife, Alfflaed, and had a younger brother and numerous sisters. He also had an older half-brother, Athelstan, who was fostered at the Mercian court with his aunt Athelflaed, but who did not seem to be the expected successor to King Edward. Alfweard’s younger brother Edwin would have been next in line to succeed Alfweard, had he not drowned in 933 AD, in circumstances which were controversial. Later it was claimed that Athelstan was responsible, but this may have been propaganda.

Alfweard also had six sisters; some of these were placed in strategic marriages to various kings and nobles when Athelstan became king. He also had two male cousins, Athelwine and Aelfwine, who were the sons of Edward´s deceased brother Athelweard. Edward the Elder’s third wife, Ecgwynn (whom he had married around 919 AD) had also given birth to two daughters, and two sons. The sons, Edmund and Eadred, did later succeed to the throne, but they would have been very young at the time of Edward´s and Alfweard’s deaths.

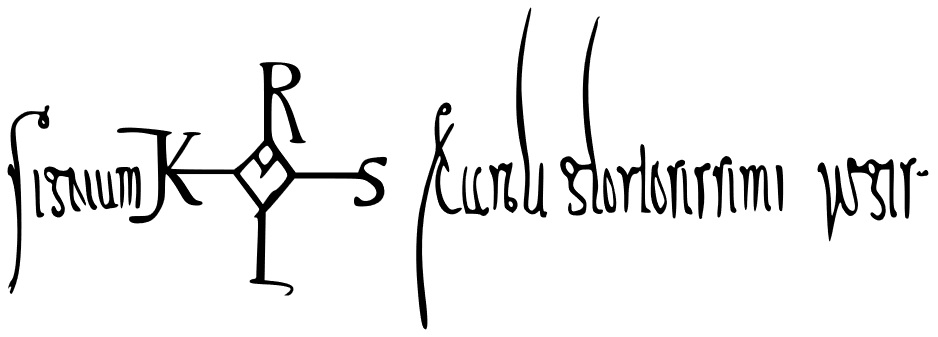

Alfweard was in his early twenties when his father died but there are rumours that he had spent some time as a hermit before returning to court. The stories tend to be later and so may be intended to reinforce Athelstan´s suitability for kingship in response to challenges to his right to rule. Alfweard witnessed a number of charters at court, with his first appearance being as early as 901 AD but the rest being consistently from 909 AD.

Following Edward’s death, Wessex had declared Alfweard as king, while Mercia favoured Athelstan who had been raised at the Mercian court under the care of Athelflaed and Athelred. There is no indication in the contemporary texts that Alfweard’s was a suspicious death, but it was certainly a convenient one for his older half-brother who had been systematically side-lined in Edward’s succession planning.

Alfweard died at Oxford on the former Wessex/Mercia border, at this time under control of Wessex. It is possible he was on his way north to meet his father´s funeral procession, or to meet Athelstan regarding the future of the two kingdoms. Another alternative is that if he really had been living as a hermit he may have been making his way back to Winchester where the Wessex court was. The most likely explanation seems to be that he was heading north to establish his authority within Mercia, which had preferred Athelstan. Edward´s death would probably have renewed the argument for the two kingdoms to separate again.

The suddenness of Alfweard´s death meant there was no time for a coronation and the records for the year are mixed in the Chronicles. Some versions fail to mention Alfweard at all, others that he died, and one with Mercian sympathies focuses on Athelstan´s coronation at Kingston.

Alfweard´s body was taken back for burial at Winchester in the New Minster. Although Edward had worked to unite Mercia and Wessex following Athelflaed´s death, removing her daughter and successor Alfwynn within a few months, it is theoretically possible he planned to divide the kingdoms between his two eldest sons. The notion of a united England was still not a foregone conclusion.

Battle of Maserfeld, 5th August 642

The Battle of Maserfeld was on 5th August 642 AD. At the battle Penda, the pagan King of Mercia, defeated Oswald, the Christian King of Northumbria and “High King” (Bretwalda) of the Anglo-Saxons.

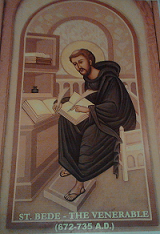

Bede tells us that:

“Oswald was killed in a great battle, by the same pagan nation and pagan king of the Mercians, who had slain his predecessor Edwin, at a place called in the English tongue Maserfield, in the thirty-eighth year of his age, on the fifth day of the month of August.

How great his faith was towards God, and how remarkable his devotion, has been made evident by miracles since his death; for, in the place where he was killed by the pagans, fighting for his country, infirm men and cattle are healed to this day. Whereupon many took up the very dust of the place where his body fell, and putting it into water, did much good with it to their friends who were sick. This custom came so much into use, that the earth being carried away by degrees, there remained a hole as deep as the height of a man.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle added that he was buried at Bardney in Lincolnshire and Bamburgh.

“AD. 642. ‘This year Oswold, king of the North-humbrians, was slain by Penda [and] the South-humbrians at Maser-feld on the nones of August [5th Aug.], and his body was buried at Bardney.

His sanctity and his miracles were afterwards manifested in various ways beyond this island, and his hands are at Bambrough, uncorrupted. And the same year that Oswold was slain, Oswiu his brother succeeded to the kingdom of the North-humbrians, and he reigned two less (than) thirty years.”

This multiplicity of resting places may appear odd but Oswald was not left intact after his death and so parts of him ended up in different locations as relics.

Bede emphasised Oswald’s saintly behaviour in his lifetime (rather than seeing him as a saint due to the manner of his death). For example he tells us about his generosity to the poor and to strangers: one time at Easter, Oswald was sitting at dinner with Aidan, and had “a silver dish full of dainties before him”, when a servant, whom Oswald “had appointed to relieve the poor”, came in and told Oswald that a crowd of the poor were begging alms from the king. Oswald immediately had his food given to the poor and had the silver dish broken up and distributed. Aidan was so impressed that he seized Oswald’s right hand, saying: “May this hand never perish.” Bede then tells us that the hand and arm remained uncorrupted after Oswald’s death.

Oswald was the son of King Athelfrith of Bernicia who was deposed by Edwin. Oswald and his family had to go into exile and he was brought up in Dal Riada where he became a Christian following the traditions of the Irish church. When Edwin was killed by Penda at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633 AD Oswald took the throne after the Battle of Heavenfield the following year, where he defeated Cadwallon and Penda.

However, Penda fought and defeated Oswald at Maserfield and dismembered his body. The cause for the battle is not entirely clear although the two kings were always wary of the each other’s power. Traditionally the location of the battle is Oswestry (“Oswald’s Tree”) which would have been outside of Northumbrian territory, indicating Oswald was probably the aggressor.

Bede claimed that Oswald’s head and body were displayed on poles, and it is possible it was a form of crucifixion. It is likely the Welsh led by Cynddylan ap Cyndrwyn of Powys were fighting with Penda. As they were Christians it is not accurate to depict the battle as a purely Pagan-Christian conflict. Penda’s brother Eowa also appears to have been killed fighting with Oswald against Penda, although his status is not at all clear; he is described as a king of the Mercians and possibly was co-ruler with Penda or even his overlord. What the battle did achieve was to cement Penda’s pre-eminence as the most powerful king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Oswald’s brother Oswiu managed to retrieve his brother’s remains the following year in a raid into Mercia.

When Oswald’s relics were brought to Bardsey the monks initially declined to receive them, being unhappy with Oswald’s overlordship of their region, indicating that he was not as universally popular as Bede tried to make out. However, Bede then tells us that a miracle soon persuaded the monks of their error.

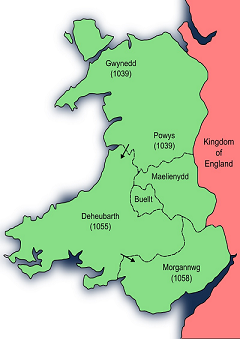

Death of Gruffydd ap Llewellyn, 5th August 1063

On 5th August 1063 Gruffydd ap Llewellyn, King of Gwynedd, was killed by his subjects. His head and ship’s beak were sent to Harold Godwinson who sent them on to King Edward (the Confessor). The Ulster Chronicle says that he was killed by Gruffudd ap Cynan, whose grandfather Iago ab Idwal ap Meurig was killed by Gruffydd in 1039 (Iago had been King of Gwynedd).

Gruffydd was the son of Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad ferch Maredudd. He became ruler of Gwynedd in 1023 when his father died and took over Powys in 1039 when its king, Iago, was killed. Iago’s son, Cynan ap Iago, was forced into exile in Dublin.

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn extended his power base in Wales until in 1056 he was recognised as the king of Wales. We discussed the Battle of Glasbury in June, where he defeated the English and was later subdued by Harold Godwinson on behalf of King Edward (the Confessor). The culmination of Harold’s campaign saw Gruffydd’s head winging its way to Edward in London.

His achievement was monumental. He was:

“the only Welsh king ever to rule over the entire territory of Wales… Thus, from about 1057 until his death in 1063, the whole of Wales recognised the kingship of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. For about seven brief years, Wales was one, under one ruler, a feat with neither precedent nor successor.”

Battle of Tettenhall, 5th or 6th August 910

The Battle of Tettenhall on either 5th or 6th August 910 AD was between Edward the Elder and the leaders of the Danelaw with victory to Edward. It is related to the Battle of Maserfield (5th August) by more than a coincidence of date. It was precipitated by a raid on Bardney Abbey by Athelflaed and Athelred to recover the relics of Oswald.

In 906 AD Edward had agreed the Peace of Tiddingford with a number of Danish leaders, updating the earlier agreement between Alfred and Guthrum. This peace held until the Mercian raid on Bardney.

Athelred and Athelflaed had been transferring their power base away from the traditional royal centre at Tamworth to Gloucester, where they built a new Minster. This removed their primary centre from the border with the Danelaw and was presumably more secure. However, the new foundation at Gloucester would have needed an important relic to attract pilgrims and enhance its status and wealth. The couple seem to have chosen the relics of Oswald, which were still held at Bardney, formerly in Mercia but now in the Danelaw. So in 909 AD they raided Bardney violating the Peace of Tiddingford. The Danes retaliated, aware that Edward was preoccupied with his fleet in Kent. However, the Danes under-estimated the speed and decisiveness of Edward’s reaction.

Sometime on the 5th or 6th August 910 AD he met them at the Battle of Tettenhall. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records:

“In this year the Angles and the Danes fought at Teotanheal on the ‘eighth of the ides of August [6th Aug.], and the Angles obtained the victory. And that same year Aethelflaed built the fortress at Bremesbyrig.”

Death of Oswine, 6th August 761

Athelwold Moll slew Oswine the Atheling in battle at Edwin‘s Cliff on 6th August 761 AD.

Athelwold Moll had taken power in Northumbria following the murder of King Oswulf two years earler (see 24th July) and was crowned on 5th August 759 AD. He was opposed by a number of the athelings and nobles, resulting in the death of Oswine who was among their number. Athelwold Moll survived as king for a few years but was eventually deposed in 765 AD.

Athelwold Moll was chosen by the Northumbrian witan as king on 5th August 759 AD, nearly two weeks after the assassination of Oswulf, the previous King of Northumbria. His background is obscure, but he was not related to Oswulf and the “Moll“ may indicate his descent from Mul, the brother of an earlier king.

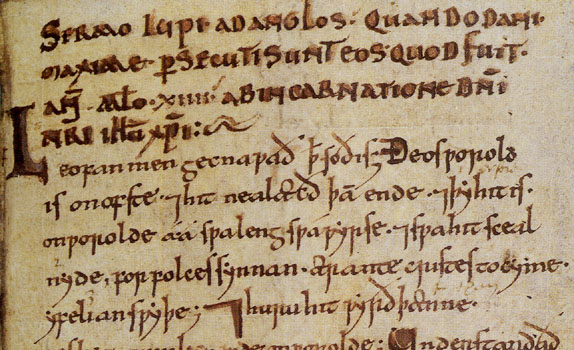

His reign was brief and inglorious. In 760 AD there was a plague; in August 761 AD he fought the Battle of Edwin´s Cliff (or Eildon Hills, according to Simeon of Durham) against Oswine, who may have been related to Oswulf. The battle lasted three days. This is the entry on the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles:

“ This year the winter was very severe; and on the 8th of the ides of August [6th Aug.], Moll, king of the Northumbrians, slew a most noble etheling named Oswin, near Edwinscliff.”

If Athelwold had been involved in the killing of Oswulf, this was probably part of an ongoing civil war.

Things improved for Athelwold in 762 AD when he married Etheldreda at Catterick on 1st November, and they had a son, Athelred Moll. However, his luck turned again and following a severe winter in 763-4 AD and subsequent famine, his men felt that this was a sign of divine displeasure and turned against him.

Oswulf’s kinsman Alhred finally drove out Athelwold on 30th October 765 AD at Finchale, near Durham, and forced him into monastic retirement.

Although Athelwold´s son Athelred Moll did become king in 774 AD, Oswulf’s son Alfwold would drive him out in turn in 779 AD, although he was back again in 789 AD until 796 AD when he was murdered.

Derby surrenders to Athelflaed, before 7th August 917

Just before 7th August 917 AD Athelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, took Derby by storm and routed the Viking invaders there.

Athelflaed had been the Mercian leader since the death of her husband, Athelred in 911 AD and had spent the intervening years building a number of defensive fortifications (burhs) on the borders of Mercia. Meanwhile her brother Edward the Elder was also building fortifications and beginning to push further into Danelaw territory.

Once Athelflaed had completed her defensive burhs she moved to take territory back, in the face of invasion by three Viking armies. She besieged Derby at the end of July and captured it by 7th August (probably the Vikings actually used the old Roman fort of Derventio nearby). Meanwhile her brother Edward attacked Colchester in Essex. The campaign was militarily successful but Athelflaed lost four of her friends in the fighting. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle explains:

“This year, before Lammas, Aethelflaed, lady of the Mercians, God helping her, got possession of the fortress which is called Derby, with all that owed obedience thereto; and there also were slain, within the gates, four of her thanes, which to her was a cause of sorrow.”

From this beginning Athelflaed started to move towards Leicester and to negotiate an alliance to take York; the local inhabitants of this Danish kingdom were not universally enthusiastic about the Norse invasions and were responding quite positively to her progress.

Her untimely death in 918 AD means we shall never know how much more successful she may have been.

Feast Day of Lide, 8th August

8th August is the feast day of St Lide. He was a hermit of the Scilly Isles who is credited with paving the way for the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason to convert to Christianity.

In the Norse saga Heimskringla it is recorded that following the death of his wife, Olaf left his homeland in 984 AD and went raiding off the Scillies where he heard about a hermit living there. Although Lide is not named in the saga, he is the man recorded as being on the island at the time and so is associated with the tale.

Olaf wanted to test the holy man so sent one of his men dressed as a king to seek advice. Lide sent him away, recognising that he was an imposter, with the advice to be loyal to his true king.

This convinced Olaf that Lide was a genuine holy man and he decided to see him in person. Lide told Olaf that he would be famous and do great deeds, and also that he would bring many people to Christian baptism. He also gave Olaf proof of his prophecy by predicting an ambush on the way back to Olaf´s ship in which Olaf would be badly wounded but would recover within seven days.

Lide’s prophecy proved correct and Olaf went back to see him again once he had recovered from the attack, even more firmly convinced of Lide’s authenticity. Lide was now able to instruct the king in Christian teachings, and Olaf and his men were all baptised.

Historically it would seem Olaf was either baptised or confirmed in 994 AD by Archbishop Alfheah; it is unclear whether he was already baptised at the time. An earlier saga by Oddr Snorrason, a 12th century Icelandic monk, also reports that Olaf was baptised on the Scilly Islands.

Lide is also known as Elid or Elidius and it is proposed that the name of St Helens in the Scilly Islands is derived from his name.

Battle of Maldon, 10th or 11th August 991

The Battle of Maldon was on or about 10th or 11th August 991 AD. Ealdorman Byrhtnoth of East Anglia was defeated by invading Vikings and a commemorative poem was written soon after. Intriguingly, in describing Byrhtnoth´s actions it has raised the question: did he lose due to pride or was he being pragmatic?

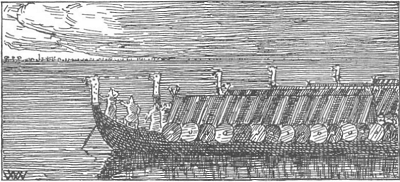

The Vikings had sailed their longships up the River Pante (now Blackwater) and beached them on Northey Island separated from the mainland by high tide. Byrhtnoth raised the English fyrd, or levy, and went to meet them and ultimately died. The poem portrays nobility in defeat, and the men as glorious and honourable at a time when the army was generally demoralised by the ongoing Viking invasions. This year was also the year when the Danegeld was first paid to persuade the raiders to attack elsewhere.

Read more about the Battle of Maldon

Death of Archbishop Jaenberht, 12th August 792

Jaenberht died on 12th August 792 AD. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 765 AD and during his tenure came into conflict with with Offa, the King of Mercia, who confiscated church lands and set up an Archbishopric of Lichfield in an attempt to increase his control over the church.

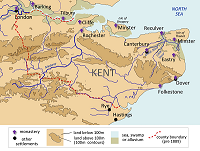

Jaenberht had previously served as abbot of St Augustine´s in Canterbury, and was consecrated as Archbishop in February 765 AD at the court of King Offa. However, he was first and foremost a Kentishman, and Offa was not a popular king in Kent. There was a rebellion there in 776 AD and Offa was defeated at the Battle of Otford. Following the battle Kentish kings issued charters independently but eventually Offa regained control of the territory. It is not clear exactly when this happened but it was around 785 AD.

However, it is probable that Jaenberht was involved in the rebellion and supported the Kentish kings. He seems to have been supportive of King Ecgberht of Kent, who granted a number of estates to Canterbury during his reign. Nevertheless Jaenberht continued to attend church councils led by Offa. After Offa reasserted his control he took the church’s lands back under the premise that Ecgberht had not had authority to give them, and instead granted them to his own thegns.

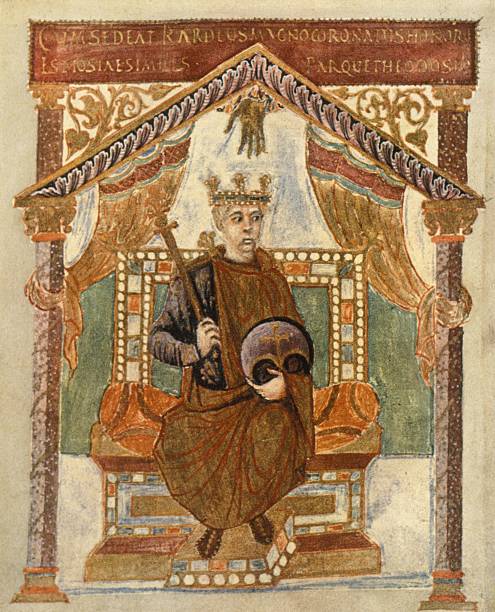

Jaenberht was rumoured by later writers, such as Matthew Paris, to have conspired to bring Charlemagne to Britain to oppose Offa, although there is no real evidence for this.

By 787 AD Offa had sent envoys to the Pope seeking the establishment of a new archbishopric in Mercia at Lichfield, having failed to move the See from Canterbury to London, which was more fully under Mercian control. The new archbishopric was agreed and Hygeberht became the archbishop, taking control of much of Canterbury´s lands and wealth, although Canterbury retained seniority (as was the case with the Archbishop of York). Pope Hadrian I had complained to Charlemagne that Offa was plotting to depose him because he had refused to move Canterbury to London, and it is possible that Jaenberht was involved in promoting this rumour. In any event Hadrian did agree soon after writing the letter to establishing the new archbishopric.

After his death Jaenberht was buried at the Abbey Church of St Augustine and soon revered as a saint.

Macbeth takes the throne of Scotland, 14th August 1040

On 14th August 1040 Macbeth killed King Duncan I of Scotland to win the throne.

Macbeth was the grandson of Ruaidri and the son of Findlaech (Finlay), and the family were the hereditary Lords of Moray. Macbeth therefore inherited the title on the death of his father. Findlaech had been killed in 1020 by his nephew, Mael Coluim, Macbeth´s cousin, according to the Annals of Tigernach:

“T1020.8 Finnlaech son of Ruaidhrí, grand steward of Moray, was killed by the sons of his brother Maelbrighde”

Mael Coluim then was succeeded by his own brother, Gilla Comgain, in 1029, and finally Macbeth succeeded in 1032. The Annals of Ulster record:

“U1032.2 Gilla Comgán son of Mael Brigte, earl of Moray, was burned together with fifty people.”

It is possible that Macbeth was responsible for his cousin´s death. He married Gilla Comgain´s widow, Gruoch, who was descended from the MacAlpin dynasty. Macbeth himself traced his descent for the Kings of Dal Riata. He became stepfather to Lulach, Gruoch´s and Gilla Comgain´s son. It was also at this time that he and Malcom of Alba submitted to Cnut of England.

Moray was a buffer state between the Scandinavian kingdom to the north and Alba to the south. However, in 1040 Duncan I King of Alba attacked Moray, apparently as a punitive expedition. He was defeated in battle at Bothnagowan (now Pitgaveny) and died near Elgin. Duncan had inherited from his grandfather Malcolm in 1034 and was still a fairly young man in 1040, with two sons, Malcolm and Donald. In 1039 he had led a disastrous expedition against Durham in retaliation for a Northumbrian attack, and 1040 proved to be no more successful. Macbeth had until then been identified as a “dux” or sub-king to Duncan. The Annals of Tigernach again:

“T1040.1 Donnchadh son of Crínan, overking of Scotland, was killed by his own immatura aetate [at a young age]”

Malcolm´s widow and sons fled Scotland and Macbeth succeeded to Duncan´s throne, apparently without any major opposition. He ruled for 17 years, mostly peacefully. However, there are records of two battles during his reign.

Firstly, Duncan´s father Crinan, Abbot of Iona, is recorded in the Annals of Tigernach as having been killed in a battle between two Scottish armies in 1045. This may have been a rebellion against Macbeth. Later in 1050 Macbeth felt secure enough to go on pilgrimage to Rome where he gave money to the poor “as if it were seed”. Then in 1052 Macbeth received a number of Norman exiles at his court, fleeing unrest in England as a result of the conflict between Edward the Confessor and Earl Godwin.

Secondly Macbeth fought Earl Siward of Northumbria in 1054 at the Battle of the Seven Sleepers (also called Battle of Dunsinane). Again we can read about it in the Annals of Ulster:

“U1054.6 A battle between the men of Scotland and the English in which fell 3000 of the Scots and 1500 of the English, including Doilfinn son of Finntor”

The battle was also of sufficient importance to be recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

“AD 1054.This year went Siward the earl with a great army into Scotland, and made much slaughter of the Scots, and put him to flight: and the king escaped. Moreover, many fell on his side, as well Danish-men as English, and also his own son.”

This battle saw the loss of Siward´s son resulting in Tostig Godwinson taking up the Earldom of Northumbria (see 27th July).

Meanwhile Macbeth continued his reign until 1057. On 15th August 1057, a day after the anniversary of his victory against Duncan, Macbeth was killed in the Battle of Lumphanan by Duncan’s son, Malcolm. Macbeth had drawn his retreating forces north to make a last stand. Macbeth’s Stone, near the site, is traditionally claimed to be the stone upon which Macbeth was beheaded, although there is no evidence for it being true. Alternatively, the “Prophecy of Berchán” has it that he was wounded and died at Scone, 60 miles to the south, some days later, and says of him:

“The red, tall, golden-haired one, he will be pleasant to me among them; Scotland will be brimful west and east during the reign of the furious red one.”

Macbeth was known as “the Red King” presumably due to his hair colour.

Initially Lulach, Macbeth´s stepson, took the throne, but Malcolm also killed him a few months later and succeeded to the throne as Malcolm III of Scotland.

Contemporary sources are generally positive or neutral about Macbeth’s reign. He was applauded for his donations to the church, and he and Gruoch made generous grants of land to religious institutions. The unusual length of his tenure indicates a stable and reasonably peaceful period, with no or limited opposition, which was remembered as a time of plenty.

Death of Roland, 15th August 778

Roland was a military leader under Charlemagne and died on 15th August 778 AD at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass when ambushed by the Basques. His story was immortalised (with poetic licence, of course) in the Chanson de Roland, an 11th century French poem.

Charlemagne had been campaigning in Spain and destroyed much of the city of Pamplona, the Basque capital, during the fighting. Charlemagne had been expanding his Frankish empire further south following the Basque submission to Pepin in the 760s, and an envoy from Sulayman al-Arabi and others seeking Charlemagne’s support against Abd al-Rahman. He besieged Zaragoza for over a month and finally negotiated a withdrawal in return for gold and the release of prisoners.

On his way back through Spain Charlemagne decided to secure control of Basque territory and ordered the destruction of the walls of Pamplona. He also attacked a number of towns in the area before making his way back through the Pyrenees to France. His rear-guard comprised a number of nobles, including Roland, to protect the baggage train and main body of men as they went.

On August 15th the Basques launched an ambush which took the Franks by surprise. They separated the rear-guard and thanks to their superior knowledge of the terrain were able to massacre the better-equipped Franks and escape with the loot from the baggage train, probably including the gold from Zaragoza. Their stand did however allow Charlemagne to move his main army to safety. This attack was arguably the only defeat suffered by Charlemagne in his military career.

Charlemagne sent his armies back in later years and succeeded in extending control in Spain eventually. He created the Marca Hispanica to serve as a buffer province between his empire and the Islamic state to the south

Later poetry has romanticised the battle out of recognition, and made Roland a chivalric hero, inspiring the later knightly code in the same way as the stories of Arthur and the Round Table did in England. The Chanson de Roland was written in its earliest form around 1040 and there are claims that William of Normandy’s men sang parts of it at Hastings to build up their courage. Oral versions also existed and probably pre-dated the written version, much like Beowulf.

In the story Roland tries to break his sword, Durandal, against a boulder in order to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. He only succeeds in breaking the boulder. In the final stage of the battle Roland sounds his horn Olifant which Charlemagne can hear 30 leagues away, and falls to the ground dead. It summons the king back to retrieve the bodies of his slain nobles and take them for burial in Frankia, and to exact revenge on their enemies.

Coronation of King Eadred, 16th August 946

On 16th August 946 AD Eadred, son of Edward the Elder, was crowned at Kingston upon Thames, following the assassination of his brother Edmund I (the Magnificent) on 26th May at Pucklechurch. He was consecrated by Archbishop Oda.

Eadred was the younger of the two sons born to Edward the Elder and Eadgifu, Edward’s third wife. Eadred’s older brother Edmund had succeeded their half-brother Athelstan in 939 AD. Eadred was born around 923 AD so would have been in his early twenties when he was crowned.

The reign started with war. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that:

“Eadred the etheling succeeded to the kingdom, and subdued all Northumberland under his power: and the Scots gave him oaths, that they would all that he would.”

The oaths may have been given at the coronation, but proved of little value. Things continued to be difficult for the king for the next couple of years:

“AD 947. This year king Eadred came to Taddene’s-scylf, and there Wulstan the archbishop and all the North-humbrian witan plighted their troth to the king: and within a little while they belied it all, both pledge and also oaths.

“AD 948. This year king Eadred ravaged all Northumberland, because they had taken Yric to be their king: and then, during the pillage, was the great minster burned at Ripon that St. Wilferth built. And as the king went homewards, then the army of York overtook him: the rear of the king’s forces was at Chesterford; and there they made great slaughter. Then was the king so wroth that he would have marched his forces in again and wholly destroyed the land. When the North-humbrian witan understood that, then forsook they Hyryc, and made compensation for the deed with king Eadred.”

Wulfstan of York was a constant challenge to Eadred and as a result Eadred dealt with him firmly in 952 AD:

“AD 952. In this year king Eadred commanded archbishop Wulstan to be brought into the fastness at Judanbyrig, because he had been oft accused to the king: and in this year also the king commanded great slaughter to be made in the burgh of Thetford, in revenge of the abbat Eadelm, whom they had before slain.”

The Kingdom of York was undergoing conflict between the incumbent ruler Eric Bloodaxe and Olaf Cuaran, who briefly seized back control in 949-952 AD but was finally ousted. Olaf had been Edmund´s godson but seems not to have received support from Eadred. However, in 954 AD Eric was also expelled by the Danes and Eadred finally won York. Wulfstan seems to have been partially forgiven and was installed as Bishop of Dorchester, safely away from his former power base.

Eadred was also a keen supporter of monastic reform and promoted Athelwold to the abbacy at Abingdon in 955 AD.

He was not a healthy man and died young, at the age of 32, without an heir. He suffered from a digestive problem which probably proved fatal. The Life of St Dunstan records how the king sucked out the juices of his food, chewed on what was left and then spat it out. He died at Frome in Somerset and was buried at the Old Minster in Winchester under the auspices of his friend and co-reformer Dunstan.

Roger of Wendover adds that Eadred called for Dunstan to come and hear his final confession:

“Eadred, the most potent king of England, was taken with a grievous sickness in the tenth year of his reign, and speedily despatched a messenger for the blessed Dunstan to receive his confession. As the latter was hastening to the palace, he heard a voice above him distinctly utter, “King Eadred now rests in peace;” whereupon the horse on which he rode, unable to bear the angelic voice, fell dead to the earth without having received any injury from his rider. On coming to the king, the blessed Dunstan found that he had died the same hour that the angel had announced it to him on his journey. The king’s body was carried to Winchester, and committed to a sepulchre by the blessed Dunstan in the Old Minster.”

Eadred´s nephew, Eadwig, succeeded him.

Feast Day of James the Deacon, 17th August

17th August is one of the Feast Days of James the Deacon (the other being 11th October).

James the Deacon was a member of the mission which accompanied Paulinus to Northumbria and York in 625 AD.

“He had with him in the ministry, James, the deacon, a man of zeal and great fame in Christ’s church, who lived even to our days.” [Bede]

Like Paulinus he was probably of Italian origin. However, when Paulinus headed south again following the defeat and death of King Edwin in 633 AD, James remained in Yorkshire. He was based near Catterick, promoting the Roman form of Christian worship with some evident success as York remained Roman despite much of the north following Lindisfarne´s Irish tradiiton. Christian activity is recorded at Catterick from this date, and fragments of a cross shaft have been found which probably pre-date the first church building. In the 8th century at least two Northumbrian kings were married at Catterick and a church was recorded in the Domesday Book in the 11th century.

Here are Bede´s words:

“He [Paulinus] had left behind him in his church at York, James, the deacon, a holy ecclesiastic, who continuing long after in that church, by teaching and baptizing, rescued much prey from the power of the old enemy of mankind; from whom the village, where he mostly resided, near Cataract, has its name to this day. He was extraordinarily skillful in singing, and when the province was afterwards restored to peace, and the number of the faithful increased, he began to teach many of the church to sing, according to the custom of the Romans, or of the Cantuarians. And being old and full of days, as the Scripture says, he went the way of his forefathers.”

James participated in the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD, which is the last reference to him in the documentation. Bede tells us that James lived “even to our days” ie late 7th century when Bede was a boy. Although he doesn’t say exactly when this happened he wrote that James died “old and full of days”.

Death of King Olaf Hunger of Denmark, 18th August 1095

18th August 1095 saw the death of Olaf I of Denmark. He was the son-in-law of Harald Hardrada, who was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 by King Harold Godwinson of England (see 25th September).

Swein Estridsson, Olaf’s father, was born in 1019, and via his mother could trace his ancestry back to Sweyn Forkbeard, the Dane who was briefly King of England after ousting Athelred Unrede in 1014. It is likely Olaf was born around 1050, as great-grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard.

Olaf succeeded his brother Cnut IV of Denmark, who had similarly held ambitions for the throne of England and had assembled a fleet against William of Normandy in 1085 but had never sailed due to domestic crises. The army wanted to disband rather than wait, and they asked Olaf to help argue their case for going home to gather the harvest. As a result Cnut arrested Olaf and exiled him to Flanders. Following an uprising in 1086 in which Cnut was killed on 10th July, Olaf became king, the third of Swein´s sons to take the throne (Cnut had succeeded their elder brother Harald). His return to Denmark from Flanders appears to have been negotiated in return for another brother taking his place there.

His reign was inauspicious and the land suffered famine. He was given the epithet “Hunger” to emphasise the calamity, and to compare his brother Cnut more favourably in an attempt to have Cnut canonised. Although the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus claimed the famine was only in Denmark, it may have been more widespread across Europe. It is not recorded elsewhere as being especially notable in Denmark apart from in sources trying to elevate Cnut.

Olaf had been in conflict with Harald Hardrada of Norway for some time but eventually married his daughter Ingegerd, as part of a treaty between Denmark and Norway, and they had a daughter.

Saxo Grammaticus claimed the Olaf willingly sacrificed himself to alleviate the famine which was God´s punishment on Denmark. Whether he killed himself or was sacrificed is unknown and his burial place is likewise a mystery.

Following his death his brother Eric became King and Ingegard returned to Norway, later marrying the King of Sweden. There were no further moves to take the English throne by Denmark´s rulers.

Death of Abbot Credan, 19th August 780

![Evesham Abbey bell tower, Oosoom [CC BY-SA 3.0]](https://www.tha-engliscan-gesithas.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/0819-Evesham_Abbey_Bell_Tower.png)

Credan was the eighth Abbot of Evesham and he died on 19th August 780 AD. He served under King Offa of Mercia and attested a number of his charters. Virtually nothing else is known about him, but he was sanctified following his death. Legend has it that he accidentally killed his own father and became a swineherd as penance. He was made a saint due to his exemplary piety thereafter.

In Ch. VII of the “Life of St Ecgwine and his Abbey at Evesham” by the Benedictines of Stansbrook, we learn that:

“We have no details of the life of St. Credan, eighth Abbot of Evesham, who flourished in the time of King Offa of Mercia, but his merit before God was revealed to Abbot Manny, who was frequently admonished in vision to take up the holy Abbot s relics and lay them in a shrine. When at length he came with great solemnity to do this, the body was found between two others, but distinguished from them by the great brightness with which it shone. The first Norman Abbot, having little faith in Saxon sanctity, resolved, by Lanfranc´s advice, to test these and other relics of the house. They were subjected to the ordeal of fire, but the fire, far from burning the sacred remains, did not so much as touch them.”

Credan had yet more miracles to perform, however. In 1207 the church tower fell destroying the sanctuary where his relics lay with those of St. Ecgwine and St. Odulf. However the three shrines were miraculously preserved.

The Abbey of Evesham was built during the opening years of the 8th century. The land was granted by King Athelred I in 701 AD and consecrated in 709 AD under King Cenred. The founder was Ecgwine, third Bishop of the Hwicce (692-717 AD) and he chose to locate the Abbey on a prominent bend in the river Avon. The location of the Abbey was originally AEt Homme, meaning “at the bend” (cf. Old English ham/hom for the bend behind the knees, hence “hamstring”).

According to Byhrtferth of Ramsey who wrote a Life of St Ecgwine, the saint had a vision of the Virgin Mary at the future site of the Abbey, where he had been taken by a swineherd named Eoves (Eof). Eoves later gave the name of “Evesham” to the Abbey.

The Kings of Mercia endowed the Abbey generously and the Abbots became very powerful in later centuries as the wealth and prestige of the foundation grew.

Assassination of King Oswin, 20th August 651

After the death of Oswald at the Battle of Maserfeld the Kingdom of Northumbria was again split into its two constituent kingdoms: the Kingdom of Deira (approximately modern-day Yorkshire) and the Kingdom of Bernicia (approximately modern day Northumberland and parts of Lothian). Oswin ruled in Deira while Oswald’s brother, Oswiu, ruled Bernicia. On 20th August 651 AD Oswin was betrayed and assassinated at Gilling in Yorkshire, allegedly at the bidding of Oswiu who then became ruler of the reunited Kingdom of Northumbria.

Oswin was the son of Osric who was King Edwin’s cousin. This made him and Oswiu second cousins with a shared great-grandfather, Yffi. When Oswin’s father died in 634 AD Oswin was still a child. He escaped to Wessex where he stayed in exile at the court of King Cynegils,and was raised as a Christian (he may already have been baptised before this). However, after 10 years he returned to claim his throne in Deira.

Bede describes Oswin in very flattering terms:

“King Oswin was of a graceful aspect, and tall of stature, affable in discourse, and courteous in behavior; and most bountiful, as well to the ignoble as the noble; so that he was beloved by all men for his qualities of body and mind, and persons of the first rank came from almost all provinces to serve him. Among other virtues and rare endowments, if I may so express it, humility is said to have been the greatest.”

Bede then goes on to relate how Oswin gave a particularly splendid horse to St Aidan to help him travel around his diocese, but Aidan gave the horse away to a beggar. Oswin was very upset when he heard about it, but Aidan rebuked him for his lack of charity and Oswiu got over his huff and begged the saint’s forgiveness for his reaction.

Oswin and Oswiu ruled jointly for a few years but eventually Oswiu declared war. Oswin however preferred not to fight, being out-numbered by Oswiu’s forces; Bede then tells us the story in more detail:

“But Oswy, who governed all the other northern part of the nation beyond the Humber, that is, the province of the Bernicians, could not live at peace with him; but on the contrary, the causes of their disagreement being heightened, he murdered him most cruelly. For when they had raised armies against one another, Oswin perceived that he could not maintain a war against one who had more auxiliaries than himself, and he thought it better at that time to lay aside all thoughts of engaging, and to preserve himself for better times. He therefore dismissed the army which he had assembled, and ordered all his men to return to their own homes, from the place that is called Wilfaresdun, that is, Wilfar’s Hill, which is almost ten miles distant from the village Called Cataract, towards the north-west. He himself, with only one trusty soldier, whose name was Tonhere, withdrew and lay concealed in the house of Earl Hunwald, whom he imagined to be his most assured friend. But, alas! it was otherwise; for the earl betrayed him, and Oswy, in a detestable manner, by the hands of his commander, Ethilwin, slew him and the soldier aforesaid, this happened on the 20th of August, in the ninth year of his reign, at a place called Ingethlingum, where afterwards, to atone for his crime, a monastery was built, wherein prayers were to be daily offered up to God for the souls of both kings, that is, of him that was murdered, and of him that commanded him to be killed.”

Unfortunately for Oswiu, Oswin was also related to Oswiu’s wife and as his nearest kin she was entitled to claim wergild in compensation for the murder of her relative. Indeed, Oswiu himself was also a relative of Oswin, so things were complicated.

The obvious solution was followed: Oswiu founded a monastery to commemorate Oswin and the monks were required to offer prayers for Oswin’s soul and for Oswiu’s salvation. The location of Gilling is not definite. It may have been Gilling West, an important centre for Deira, and the site of the discovery of the Gilling Sword. The monastery may have been Gilling Abbey near Gilling West. However, there are some historians who prefer Gilling East as the location, both being in Yorkshire.

Wherever it was, Oswin’s remains were soon taken from Gilling to Tynemouth Priory where their location became forgotten. Then in 1065 a vision was granted to a monk called Edmund. Oswin came to him in a dream to indicate where his mortal remains could be found, saying to him:

“I am king Oswin slain by Oswy through the detestable treachery of count Hunwald, and I lie in this Church unknown to all. Rise therefore and go to the bishop Egelwin, and tell him to seek my body beneath the pavement of this oratory, and let him raise it up and re-inter it more becomingly in this same chapel”

The remains were duly located by the authorities and later venerated by Tostig Godwinson, Earl of Northumbria, and his wife, Judith of Flanders, who washed Oswin’s hair which was still stained with blood. In 1103 Oswin was moved again, this time to St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire.

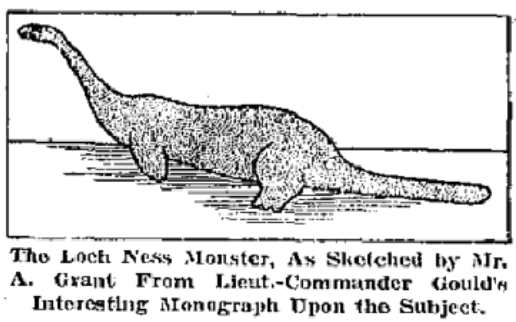

Columba and the Loch Ness Monster, 22nd August 565

St Adomnan wrote a Life of St Columba in which he described how an aquatic monster was driven off by Columba. This was the famous Loch Ness Monster and the date of its encounter with Columba was 22nd August 565 AD. Here is what Adomnan wrote:

“On another occasion also, when the blessed man was living for some days in the province of the Picts, he was obliged to cross the river Nesa (the Ness); and when he reached the bank of the river, he saw some of the inhabitants burying an unfortunate man, who, according to the account of those who were burying him, was a short time before seized, as he was swimming, and bitten most severely by a monster that lived in the water; his wretched body was, though too late, taken out with a hook, by those who came to his assistance in a boat. The blessed man, on hearing this, was so far from being dismayed, that he directed one of his companions to swim over and row across the coble [boat] that was moored at the farther bank. And Lugne Mocumin hearing the command of the excellent man, obeyed without the least delay, taking off all his clothes, except his tunic, and leaping into the water. But the monster, which, so far from being satiated, was only roused for more prey, was lying at the bottom of the stream, and when it felt the water disturbed above by the man swimming, suddenly rushed out, and, giving an awful roar, darted after him, with its mouth wide open, as the man swam in the middle of the stream. Then the blessed man observing this, raised his holy hand, while all the rest, brethren as well as strangers, were stupefied with terror, and, invoking the name of God, formed the saving sign of the cross in the air, and commanded the ferocious monster, saying, “Thou shalt go no further, nor touch the man; go back with all speed.” Then at the voice of the saint, the monster was terrified, and fled more quickly than if it had been pulled back with ropes, though it had just got so near to Lugne, as he swam, that there was not more than the length of a spear-staff between the man and the beast. Then the brethren seeing that the monster had gone back, and that their comrade Lugne returned to them in the boat safe and sound, were struck with admiration, and gave glory to God in the blessed man. And even the barbarous heathens, who were present, were forced by the greatness of this miracle, which they themselves had seen, to magnify the God of the Christians.”

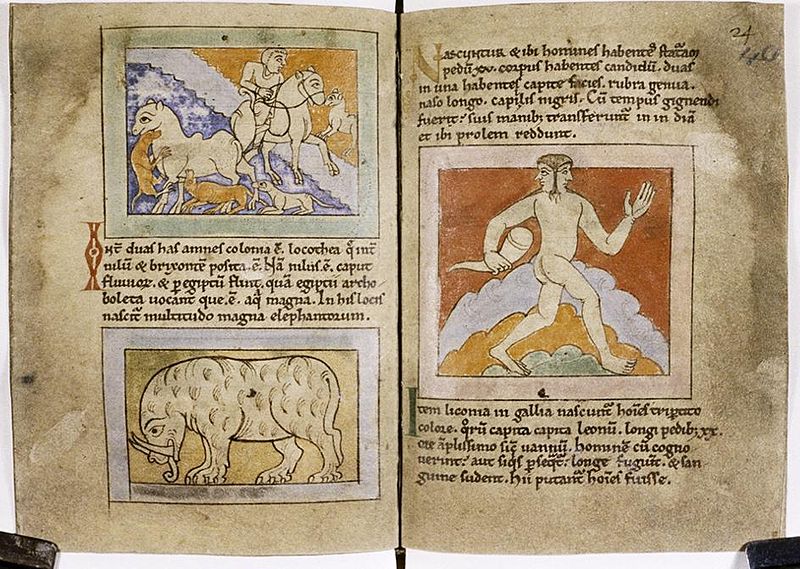

The medieval mind viewed things differently from us. If you could imagine something then it was possible and so, in a sense true. One of the manuscripts which has survived from this period is called “The Wonders of the East”. It describes strange and terrifying creatures encountered by travellers in distant lands. The earliest version of the manuscript is part of the Nowell Codex, which also includes the poems Beowulf and Judith. The collection as a whole has a theme of “monsters”; Beowulf is described as one and also fights various monsters, and Judith acts in a monstrous fashion against the even more monstrous Holofernes.

The monsters depicted in the lands to the East include dragons, gold digging ants, strange half-human creatures with gigantic ears or faces in their chests, phoenixes, and hens which would burn anyone who touched them.

Other versions of the book exist in the Bodleian collection and the Cotton Tiberius collection at the British Library. The monsters vary between manuscripts but all are based on earlier continental Latin texts of Greek origin, although presented in a different format.

It is arguable whether the texts are for entertainment purposes, or encyclopaedic, or represent a purpose not really understood by the modern reader. However, the various copies over an extended period certainly emphasise the enduring popularity and interest in their subject matter.

Sack of Rome, 24th August 410

On 24th August 410 AD Alaric I led the Visigoths to the Sack of Rome. This soon resulted in the permanent withdrawal of troops from the Roman Province of Britannia and heralded the beginnings of the Anglo-Saxon Age over the next 600 years.

So who was Alaric and why did he sack Rome?

Alaric was a Visigoth who served in the Roman Army. He led a group of Gothic warriors on an invasion of Thrace in 391 AD but was defeated by the Roman General Stilicho. He later led his men in support of the Emperor Theodosius but when he failed to receive recognition for his talents he left the Romans and was elected the leader of the Visigoths. From then he led his army across Greece, attacking a number of cities. His lack of recognition by the Roman Emperor in the West was not reflected in the Eastern Roman Empire where the Emperor Arcadius put him in charge of the army.

Alaric then moved to invade Italy and was again defeated by Stilicho. After that he stayed in the East for the next few years. In 408 AD the Western Roman Emperor Honorius executed Stilicho on the basis of rumours that he had reached an agreement with Alaric. Honorius then went on to massacre the families of Goths serving in the Roman Army which inevitably resulted in a surge of Goths defecting to Alaric´s army. Alaric moved on Rome seeking revenge, ravaging as he came. Laying siege to Rome, he was paid off by the Senate and also able to demand the liberation of Gothic slaves in the city. However, he was still denied the leadership of the army – perhaps not surprisingly.

The following year Alaric again besieged Rome and elevated Priscus Attalus to Emperor. Attalus knew what he had to do, and made Alaric leader of the military. However Alaric still was unable to do exactly as he wished and was denied the opportunity to invade Africa. Honorius continued to block Alaric and Attalus, and finally in 410 AD Alaric removed Attalus and besieged Rome once more.

The gates of the city at Porta Salaria were opened to him on 24th August 410 AD, possibly by supporters, and for three days Alaric’s troops looted and plundered the city. However, there are numerous records, written by surprised churchmen, of the restraint the Goths showed in dealing with the inhabitants of the city. They wanted treasure but did not resort to undue violence against people sheltering in the churches. Nor was there widespread destruction of buildings although some archaeological evidence for fires have been linked to the events of 410 AD.

The writer Jordanes, for example, wrote in his Getica (History of the Goths) that:

“by Alaric’s express command they merely sacked it and did not set the city on fire, as wild peoples usually do, nor did they permit serious damage to be done to the holy places.”

Alaric finally moved south towards Africa, vital for its grain supply to Rome. However his fleet was destroyed in a storm and Alaric himself died, probably of malaria, soon afterwards. He was allegedly buried under a river bed with treasure (the river was temporarily diverted while the grave was dug).

Although the Sack of Rome was relatively swift and the city relatively undamaged, the consequences of the attack were significant. Rome struggled on until it fell to Odoacer more than 50 years later, and troops from the provinces were recalled as defence of the Eternal City became the priority for the Empire. Meanwhile the Romano-British were told to look to their own defences as their garrisons drained away.

Death of Aebbe the Elder, 25th August 683

25th August is the feast day of Aebbe the Elder who died on this day in 683 AD.

She was a saint, an abbess and a sister to Oswald and Oswiu of Northumbria, along with five other brothers. She was still a child, perhaps only a couple of years old, when Athelfrith of Northumbria was killed in battle by Edwin of Deira in 616 AD by the River Idle. Her family fled north to Dal Riata where they remained in exile under the protection of the king until Oswald reclaimed his throne in 634 AD.

The children were accordingly brought up as Christians according to the Irish Church and Aebbe was devout. A Scottish prince, Aidan, wanted to marry her and her family were keen that she take up the offer. However, she took the veil instead from St Finan, Bishop of Lindisfarne, around 655 AD. Her brother Oswiu, by now the King, recognised her determination and gracefully gave her land to build her first monastery at Ebchester (Aebbe´s camp). Later she founded the monastery at Coldingham where she became the Abbess and presided over a double house for men and women. It stood on St Abb´s Head (which also preserves her name). Among her visitors were Cuthbert, Prior of Melrose and later Abbot of Lindisfarne, for whom she personally wove a piece of cloth in which he was later buried.

It was during his visit that Cuthbert’s miracle with the otters was witnessed. Briefly Cuthbert went each night down to the shore and walked into the icy water until it reached his neck. He then spent the night singing psalms and praying. On coming out of the water in the morning, two otters came and dried and warmed his feet. This is why Cuthbert is often portrayed with an otter in iconography.

Another visitor was queen Alfthryth, wife of Aebbe´s nephew King Ecgfrith, who fled her husband to return to East Anglia and found Ely Abbey. She went to Coldingham for help in her escape, having been tutored by Aebbe.

Aebbe´s third visitors of note were her nephew Ecgfrith, this time with his new wife Ermenburga. During their stay Ermenburga suffered severe pains and Aebbe explained these were due to the couple´s treatment of St Wilfrid who was currently imprisoned by them and whose reliquary Ermenburga had taken and carried everywhere with her. Upon Wilfrid’s release and the return of the reliquary the queen recovered her health.

Sadly for Aebbe the monastery´s reputation left much to be desired. Discipline was surprisingly relaxed for such a devout Abbess. Aebbe was consistently regarded as wise, pious and devout despite the activities happening under her leadership. One of the monks, Adomnan, predicted that the monastery would be destroyed by fire. This is how he described it to Aebbe:

“but all of them, both men and women, either indulge themselves in slothful sleep, or are awake in order to commit sin; for even the cells that were built for praying or reading, are now converted into places of feasting, drinking, talking, and for their delights; the very virgins dedicated to God, laying aside the respect due to their profession, whensoever they are at leisure, apply themselves to weaving fine garments, either to use in adorning themselves like brides, to the danger of their condition, or to gain the friendship of strange men; for which reason, a heavy judgment from heaven is deservedly ready to fall on this place and its inhabitants by devouring fire.“

However he did reassure Aebbe that this would not occur during her lifetime. The monks and nuns attempted to improve their behaviour as a result of this dire prediction and succeeded for a while. However, after Aebbe´s death they reverted to their old ways and the monastery duly burned down in 683 AD.

Confusingly there was a second Abbess called Aebbe in the 870s, and she is generally referred to as Aebbe the Younger.

In March 2019 it was suggested AEbbe´s monastery may have been found, near or under Coldingham Priory as radiocarbon dating of animal bones placed remains firmly in the appropriate period (664-864 AD). The conclusion of the archaeological work was that:

“The increasing body of evidence within the heart of Coldingham strongly supports the hypothesis that the site is the location of the early monastic community established by St. Aebbe.”

Crowland Abbey destroyed, about 26th August 870

Sometime around 26th August 870 AD the monastery at Crowland (also called Croyland), the retreat of St Guthlac in the 7th century, was ravaged and destroyed by Danish invaders. The first monastery was founded in memory of St Guthlac, who began his life as a hermit on 24th August (St Bartholomew’s Day) probably around 699 AD.

According to Stanton’s Menology:

“The year 870 is especially memorable for the cruel outrages of the pagan Danes, who in different parts of the country slaughtered innumerable victims, in their thirst for conquest and hatred of our holy religion, choosing in preference ecclesiastic and religious of both sexes. Lincolnshire and East Anglia were among the provinces which suffered most, and there, shortly before the glorious martyrdom of St Edmund, the chief monasteries were utterly destroyed.”

This was only months before the Year of Battles (870-871 AD) which concluded in Alfred becoming King of Wessex and eventually in 880 AD the Danish War Leader Guthrum taking baptism and becoming ruler in East Anglia, where Crowland is to be found. King Edmund of East Anglia had been martyred by the Danes in November 869 (see 20th November) while they overwintered at Thetford. They then moved against Wessex and engaged at the Battle of Englefield on 31st December. This was followed by the battles of Reading (4th January 871), Ashdown (8th January), Basing (22nd January) and Meretun (22nd March). Alfred succeeded as King of Wessex on 23rd April 871 and paid the Vikings off.

Stanton continues with more detail about the attack on Crowland:

“It was on the 26th or 30th of August that the barbarians reached Croyland, the celebrated retreat of St Guthlac. The solemn Mass was just ended but the clergy had not left the sanctuary, when the pagans broke into the church. The celebrant, who was the Abbot Theodore, the Deacon Elfgetus, and the Sub-deacon Savinus, were murdered in the sacred vestments before the altar, and shortly afterwards the Acolyths Egdred and Ulrick. Some of the community escaped, and hid themselves in a neighbouring forest; but those who sought to conceal themselves within their own walls seem all to have been discovered and cruelly butchered. Amongst these were Askegar, the Prior, and Sethwin, the Sub-prior, as well as two venerable monks, Grimkeld and Agamund, who had attained their hundredth year. The shrine of St Guthlac was profaned, and the holy place left in a state of complete desolation.”

Other chronicles record the events in 867 AD rather than 870 AD but the names of those involved are the same. Many of the names of those massacred are noted as having a Danish derivation, emphasising that Scandinavian settlement of East Anglia (as elsewhere) was well established. A boy who was present at the massacre, Turgar (Thorgeir), was taken prisoner by the attackers to be sold as a slave, but managed to escape and make his way to Ely. Once there he told the monks what had happened and they recorded it all. This is why we have the level of detail today.

The leader of the attackers was Oskytel, and it was he who killed Theodore before the altar. Jarl Sidroc (Sigtryg) was the one who took Turgar prisoner.

Feast Day of Pandwyna, 26th August

Stanton’s Menology (1892) records for 26th August “At Eltisley, in Cambridgeshire, the commemoration of ST. PANDWYNA, Virgin.”

Details about the saint are scarce, and follow a familiar pattern of a young woman who wished to lead a religious life being pressured into marriage, presumably for dynastic purposes. Pandwyna is interesting because although she finished her career in Cambridgeshire, she was originally Scottish or Irish. Here is what Stanton says about her:

“ST. PANDWYNA, or PANDONIA, was the daughter of a prince of Ireland or North Britain, 904 c. who fled to England to escape the tyranny of her father and the pursuit of those who would have compelled her to abandon her purpose of serving God in the state of holy virginity. She took refuge with a kinswoman of hers, who was prioress of a nunnery at Eltisley in Cambridgeshire.

There she led a life of great perfection, and obtained the reputation of eminent sanctity. She was buried near a well, which bears her name, and at a later period her sacred relics were translated to the parish church, which still bears the title of St. Pandonia and St. John the Baptist.”

Unfortunately he does not say (or know) who the kinswoman was, how she came to be in East Anglia, how long Pandwyn lived there, or how her father or bridegroom reacted. It seems that her death was c. 940 AD and that 26th August is her Feast Day and so potentially her date of death (although this is not definite). A local legend records that she appeared in a vision to some children, possibly to show them the location of the well which took her name, and this vision resulted in her canonisation.

Her remains were translated inside the Church (which dates to about 1200) and buried beneath the altar in 1344. Apparently in the 16th century the well was filled in by the local clergyman and is now lost along with the site of the nunnery itself:

“The vicar… Robert Palmer, who was charged before the Consistory court in 1576 with many misdemeanours. Amongst them… that he had broken the stonework round a well in the churchyard to the great danger of children playing in the churchyard. To the latter he replied “that it was a well used for superstitious purposes, therefore he broke it down”

We don’t know what the purposes were, but clearly they were sufficiently serious for this rather eccentric cleric to consider the lives of local children worth the risk!

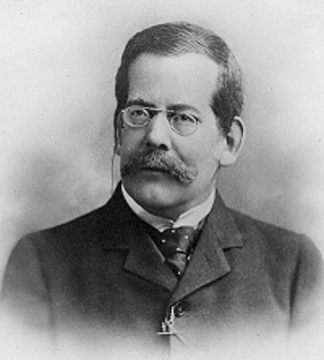

Birth of Doris Mary Stenton née Parsons, 27th August 1894

27th August 1894 saw the birth of the important medievalist Doris Mary Parsons in Reading, Berkshire. She was the only child of John Parson and Amelia Wadhams.

Doris attended the Abbey School in Reading. According to Kathleen Major, who wrote a biography, Doris “had a certain satisfaction in having proved that she had far exceeded the expectations of her headmistress”. However, she repaid her debt to the school in later years by serving as a governor and Honorary Secretary to its Council.

She entered the University College at Reading in 1912 as a day student, cycling in to the college from Woodley each day (about 2-3 miles each way).

Frank Stenton, the medievalist, was lecturing in history and Doris described his first lecture as “like the opening of windows”. Even before taking her finals she started cataloguing coins and she earned a first class degree in 1916.

In 1917 she obtained an assistant lectureship at the University College in Reading. She was also engaged in the transcription of the charters at Lincoln Cathedral

She married Frank in 1919 and was able to continue lecturing as the university did not prevent married couples from working in the same department and the two Stentons were able to encourage one another and develop their careers together.

In 1924 she was instrumental in the revival of the Pipe Roll Society. The Society had originally been founded in 1883 by the Public Record Office to oversee the systematic publication of the Pipe Rolls which are the financial records of the Exchequer or Treasury dating back to the 12th century. Doris was the Honorary Secretary and General Editor from 1925 until 1962. Her work for the Society was recognised by the publication in 1962 of “A Medieval Miscellany for Doris Mary Stenton” containing papers by friends and students on areas connected to her work.

She became a Fellow of the Royal Academy in 1953 and served on the Council of the Selden Society (1957-1969), the Council of the Royal Historical Society (1943-46 and 1947-51 and as Vice President 1953-57).

She was Lecturer, Senior Lecturer and Reader in History at the University of Reading from 1920 to 1959. Her major works are “English Society in the Early Middle Ages (1066–1307)” (1951) and later editions, and “The English Woman in History” (1957) in which the Anglo-Saxon approach to women as opposed to that of the Normans won her commendation. Her article on the Magna Carta first appeared in the 14th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1929.

In 1948 she received a D.Litt. as the first person at Reading to take this degree on the basis of her published work. She served on the Committee for Women’s Halls, the Museum of English Rural Life and the Joint Committee for Training Colleges. In 1958 she received an honorary degree from Glasgow and in 1968 from Oxford.

She was invited to present the Jayne Lecture for the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia in 1963 which was published as “English Justice between the Norman Conquest and the Great Charter”.

Her own academic focus was on the period following the Norman invasion, but after the death of her husband on 1967 she completed the publication of the third edition of his monumental work “Anglo-Saxon England” with Professor Dorothy Whitelock. She also saw through the publication of “The Free Peasantry of the Northern Danelaw”. She then completed a memoir of Sir Frank for the British Academy.

However she found life hard from then on, with little to engage her interest. Although enjoying visits from friends and the support of various helpers, she was increasingly isolated by growing deafness and some heart problems. She died in 1971 following a stroke.

She was described by Sir Maurice Powicke, medieval historian and Fellow of Merton College Oxford as follows:

“She is a true historian as well as a fine editor and palaeographer and her insight like a good lamp burns with a clear and steady flame.”

Battle of Isonzo, 28th August 489

The troubles afflicting the Western Roman Empire had consequences for the island of Britain, so let’s take a look at one of the key battles that happened in the 5th century. Alaric’s attacks on Rome depleted the province’s military strength after 410 AD (see 24th August). However, the turmoil continued for generations and were recorded in Anglo-Saxon poetry.

The Battle of Isonzo (Aesontius ) was fought on 28th August 489 AD and Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths, defeated Flavius Odoacer who retreated and Theodoric entered Italy. They clashed again at Verona at the end of September.

Odoacer was an East Germanic barbarian warlord serving in the Roman Army. He deposed the emperor, founded the Kingdom of Italy and made himself its first king in 476 AD. His reign is generally seen as marking the end of the Roman Empire in the West. He stabilised the Romans despite styling himself as a client of the Eastern Emperor. He supported a campaign to depose the Emperor Zeno in 487-88 AD and Zeno engaged Theodoric to remove him.

Theodoric was born in 454 AD in the Roman Province of Pannonia, the son of King Theodemir of the Ostrogoths. However, he grew up in Constantinople as a hostage in order to secure Gothic compliance with a treaty made with Constantinople. He received an imperial education before succeeding his father in 474 AD.

He led his people against the Thracian Ostrogoths, defeated Strabo and united the two peoples in 484 AD. The Emperor awarded him with military honours before ordering him to defeat Odoacer in 488 AD. Theodoric led his troops (including Goths, Rugians and Romans) across the Alps and met Odoacer at the River Isonzo on 28th August 489 AD.

Theodoric and Odoacer engaged in a four year struggle following the battles at Isonzo and Verona until Theodoric finally killed his enemy with his sword while they feasted to celebrate a treaty to rule jointly in Italy. He then settled their combined people in Italy with his capital at Ravenna.

Things started to fall apart for Theodoric around 522 AD and in 523 AD he had the philosopher Boethius, so beloved of Alfred and many Anglo-Saxon scholars, imprisoned and executed.

Theodoric died on 30th August 526 AD in the mausoleum on Ravenna, struck by lightning, on the very day he had ordered the Roman Catholic churches in his empire to surrender to the Arian interpretation of Christianity. This was not seen as a coincidence by many.

He then entered Germanic legend as Dietrich of Bern. He also appears in Norse sagas and in Anglo-Saxon poetry. In this persona he was supposed, among other things, to have been exiled for 30 years which might just be a reference to his time serving under the Emperors in Constantinople before he took the Kingdom of Italy.

In the poem Deor he is mentioned briefly and somewhat ambiguously:

“Theodric ruled for thirty winters

The city of the Maerings (famous men); that was well known to many.

That passed over so can this.”

In the legend of Dietrich he suffers exile for 30 years and then returns to win back his throne in Italy and Ravenna. One academic has argued that the translation of “Maeringa burg” could refer to the warband instead, a “city of famous warriors”, which served his exile with him.

In the poem Widsith he is listed as ruling the Franks in the section containing villainous kings (Attila, Ermanric, Becca, Gifica and so on).

Finally he appears in the story of Waldere, where Hagena turns down the offer of the sword Mimming, saying his own is better as it was the one given to Widia by Theodoric as a reward for rescuing him from the clutches of giants.

Theodoric’s poor press was due in part at least to his treatment of Boethius. Alfred translated Boethius’ “Consolations of Philosophy”, which was written in prison, as one of the books “most needful for me to know”.

Feast Day of Edwald of Cerne, 29th August

29th August is the Feast Day of St Edwald of Cerne who died around 900 AD.

Edwald is alleged to be the brother of King Edmund the Martyr, who was slain by Danish invaders in East Anglia. Edwald is not otherwise attested as a king in East Anglia so the link to Edmund remains unsubstantiated. Coin evidence indicates that Edmund was succeeded by Oswald, and then Athelred, before Guthrum returned in 880 AD.

Nevertheless Edwald is said to have left his homeland around 871 AD and lived as a hermit near Cerne in Dorset by a spring called Silver Well. On his way to Dorset, he had a vision of a silver well, and started trying to find it. When he got to Cerne he gave a shepherd some pennies for bread and water, and the shepherd took him to a well. Edwald recognised it as the one in his vision, and built a hermitage there. He lived on bread and water in his cell and worked many miracles.

The well itself has a number of stories connected to it, and is in some traditions linked to St Augustine. It can cure problems with the eyes, infertility, and help sickly newborns. Girls used to be told to place their hands on the wishing stone and pray to St Catherine for a husband. Finally if you look in the well first thing on Easter Day, then you will see those who will die that year reflected in the water.

In 987 AD a monastery dedicated to St Peter was built nearby and Edwald’s remains were duly translated there. The Abbey was founded in the late 10th century and was the home for some time of Alfric of Eynsham. The wealth of the abbey recorded in Domesday , when it was the third richest abbey in western England, was possibly due to the popularity of Edwald´s shrine.

Feast Day of King Saebbi, 30th August

30th August is the Feast Day of an Essex king and saint, Saebbi, who rather unusually for the time, seems to have died in his bed.

Saebbi was a joint King of Essex with his cousin Sighere, both ruling as sub-kings to Wulfhere of Mercia. They succeeded Swithelm who was baptised by Cedd at Rendlesham.

Sigehere abandoned Christianity and began restoring the temples of the old religion. However, Saebbi remained a convert to the new faith.

Their overlord Wulfhere sent a bishop to the kingdom to try and restore the faith with some success. Sighere died in 683 AD and Saebbi ruled both parts of the kingdom alone until 694 AD when he decided to retire to a monastery due to ill health.

Throughout his reign he practised good works, being faithful in his prayers and giving generously to the poor. He had wanted to retire sooner but his wife could not be persuaded.

Bede tells his story: