Death of Queen Mathilda, 2nd November 1083

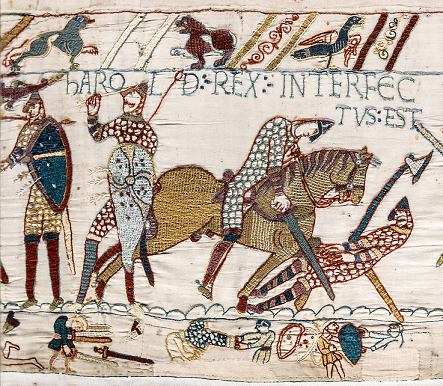

2nd November 1083 saw the death of Mathilda of Flanders, the wife of William of Normandy.

She was the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders, and through him she could trace her ancestry back to Alfred of Wessex and Charlemagne. Born in the early 1030s (the year is not known for certain), she grew up in Bruges and may possibly have met Emma, twice Queen of England through marriages to Athelred Unrede and Cnut, when she was in exile during the reign of Harold Harefoot. Emma remained at Baldwin’s Court until 1040.

Orderic Vitalis praised Mathilda’s intelligence and learning; it is possible she learned Latin although she did not learn to write. (Reading and writing were very separate activities at this time, and some copyists could not read, which may account for some of the errors in medieval manuscripts.) She was also graceful and devout, but it seems she had an independent streak. As a princess she would have been expected to be married off to support a dynastic alliance. However, according to the Annals of Tewkesbury Abbey, it would seem that she fell for an English nobleman, Brihtric Meaw of Gloucester, and declared she wished to marry him. Brihtric turned her down and it is sad to say that she exacted revenge later.

A marriage with William Duke of Normandy was proposed and although her father tried to persuade her, Mathilda was not interested due to his illegitimacy. There is an apocryphal story of William attacking her on her way back from Mass, and either beating her or raping her, but it seems unlikely that anything quite so outrageous would have been allowed to pass by her father without strong reprisals. However, in the end Mathilda changed her mind and agreed to marry the Norman Duke. It is interesting William was known for remaining faithful to Mathilda for their entire marriage and never fathering a bastard himself, behaviour which was considered unusual for nobles of the time.

Their marriage was unconventional in other ways; they required Papal dispensation due to alleged consanguinity as they were first cousins once removed, although not through a direct bloodline. However, it is most likely they went ahead and married around 1050 without Papal approval despite this meaning their children would be considered illegitimate. They witnessed a charter together in 1051 with their infant son Robert. The dispensation was not given until around 1059.

Their sons were Robert, Richard, William “Rufus” and Henry; their daughters probably Constance, Matilda, Adeliza (Adelaide), Cecilia and Adela, although the definitive names and numbers of all the daughters is not entirely clear.

The marriage seems to have been successful and generally loving. When William was seriously ill shortly before 1066, Mathilda became distraught and offered 100 shillings at the altar of Coutances Cathedral for his recovery. This did not mean they were always in agreement and stories of violent arguments were recorded.

The Godwin family was exiled from England in 1051, and it was during this time that it is later alleged that Edward offered the succession to William. Godwin found refuge in Baldwin’s court in Flanders and was able to enlist support to return to England in 1052.

According to Eadmer of Canterbury (an 11th century ecclesiastic), in 1064 Harold Godwinson arrived at William’s court to visit, and probably to negotiate the release of, his brother Wulfnoth and his nephew Haakon Sweynson, who had been hostages there for some years. They had originally been hostages at Edward’s court during the events of 1051 to secure Godwin’s good behaviour, and seem to have been taken to Normandy when the Norman members of Edward’s court returned there in 1052 following the reinstatement of Godwin and his sons. Mathilda is likely to have met Harold during his visit and allegedly Harold discussed the possibility of his marrying one of their daughters with her, resulting in William becoming jealous of the time they spent together.

Prior to the invasion of 1066, Mathilda secretly built a longship for William which she fitted out and named “Mora”. William was thrilled and immediately made it his flagship and promised Mathilda the revenues of Kent once he was successful in his enterprise. During his absence Mathilda was left to govern Normandy, so firm was William’s faith in her abilities. Their daughter Adela was born soon after the Battle of Hastings, the first of their children to have “royal blood” due to William’s enhanced status as king.

Once her husband had subdued the English sufficiently he felt it was safe to bring Mathilda to England to be crowned as Queen, and this was done at Easter 1068. Although English Queens had been crowned before as consorts of kings, Mathilda was the first to be crowned and anointed separately from her husband.

Mathilda heard pleas with William in court and gave judgements with him, as she had previously done in Normandy as duchess, and witnessed numerous royal charters. William also left her to hear lawsuits about land disputes in his place.

The year of her coronation, 1068, was also the year of the Revolt of the Earls in the north. William rode north, building a castle at Nottingham and two in York (Clifford’s Tower remains today). According to tradition Mathilda followed him and give birth to Henry at Selby in Yorkshire, south of York.

Also in 1068 we meet again Mathilda’s first love, Brihtric. According to the records of the Abbey at Tewkesbury:

“Hayward’s son, Earl Algar, inherited the patronage of Cranbourn and Tewkesbury, and on his death it passed to his son Berthric, or, according to the Isham MS., Britricus Meawe. This Britric, while on an embassy in Flanders, refused the hand of the Earl’s daughter Matilda, who was subsequently the wife of William Duke of Normandy, the conqueror of England. When the lady became Queen of England in 1068 she had Britric’s manors confiscated, and he died in prison at Winchester. Thus Tewkesbury passed into the hands of the Normans.”

However, Brihtric’s lands were closely linked with Gytha, widow of Godwin and mother of Harold Godwinson, so it is possible he supported her rebellion at Exeter, which would have given William reason enough to take his land.

In 1069 William sent Mathilda back to Normandy for safety and to manage his affairs while he remained in England.

In 1072 their son Richard was killed in a hunting accident in the New Forest while still relatively young, probably in his teens. She had already lost her daughter Agatha (the girl supposedly betrothed to Harold Godwinson and later to Alfonso, King of Leon). By 1079 her husband and son Robert were at each other’s throats, causing her great unhappiness. She rather unwisely supported Robert with money and advice against William and was found out. He forgave her eventually but she no longer argued Robert’s case and her retainer who had been involved in the affair was executed. The rift was not healed until 1080.

Mathilda was always a generous benefactor to the church and when she died had relatively little personal wealth, having given much of it away. Part of her epitaph reads:

“She was the true friend of piety and soother of distress, enriching others, indigent herself, reserving all her treasures for the poor; and by such deeds as these, she merited to be a partaker of eternal life, to which she passed November 2 1083.”

Feast Day of Rumwold, 3rd November

3rd November is the Feast Day of Rumwold, an Anglo-Saxon saint who is not well known. This may be because he only lived for 3 days.

According to Alban Butler:

“His father was king of Northumberland, his mother a daughter of Penda, king of the Mercians. He was born at Sutthun, and baptized by Widerin, a bishop, the holy priest Eadwold being his godfather. He died very young on the 3rd of November and was buried in Sutthun by Eadwold. The year following his remains were translated by Widelin to Brackley in Northamptonshire, and on the third year after his death to Buckingham where his shrine was much resorted to out of devotion. The 28th of August was celebrated at Brackley, probably the day of the translation of his relics.”

However, there was also an 11th century hagiography (Saint’s Life) about the child which provides more information.

The Vita S. Rumwold claims that he was born as the grandson of Penda and the son of a Northumbrian king, which is already difficult to square with the known facts. Ahlfrith of Northumbria did indeed marry Cyneburh, daughter of Penda, but he was King of Deira under his father Oswiu. When he disagreed with Oswiu he was replaced by his brother Ecgfrith.

The baby was miraculously able to speak from birth, repeating at least three times “I am a Christian”, demanding baptism and Holy Communion, and preaching to those around him about Wisdom and the Trinity. He then predicted his own death and finally instructed that he be laid to rest in Buckingham (after spending time at King’s Sutton or Brackley).

The Vita explains:

“in a pleasant field, filled with lilies and roses, the servants and soldiers eagerly spread out the camp and the tents, and soon the queen gave birth to the son longed for by many, and sanctified by God. When the baby was born, he immediately cried out with a loud voice: “I am a Christian, I am a Christian, I am a Christian!”. To this Widerin and Eadwald, two priests, responded: “Thanks be to God”. The child went on and said: “I worship God the three in one. I confess and adore the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit”. The priests and parents and all who were present marvelled and began singing the ‘Te Deum Laudamus’. At the end of the hymn, the child asked to be made a catechumen by the priest Widerin, to be held aloft for the preliminary rite of the faith by Eadwald, and to be named Rumwold.”

It then describes his requirements for the care of his remains:

“Rumwold required that his body remain at his birth place for one year, and then at Brackley for two years and finally be taken to Buckingham where it should rest for all time.”

His feast day is recorded in 10th century liturgical calendars so was known by then, although he seems to disappear from most calendars after 1066, indicating a general lack of support for his cult.

He was also commemorated in Sweden, where he is mentioned in fragments of a 12th century missal and a breviary. It seems likely that the English missionary work in Sweden in the 11th century may have exported his story before it faded away in England, and the prayers probably therefore derive from English ones.

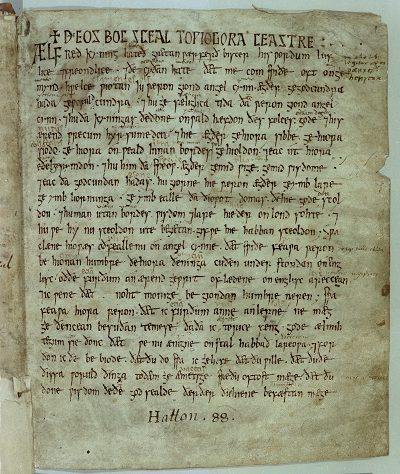

An 11th century list of saints’ resting places includes Rumwold:

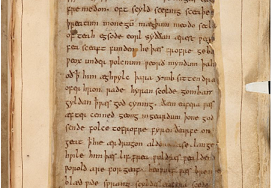

“THonne resteth sancte Rumwold on thaere stowe, the is gehaten Buccyngaham, neah thare ea Usan“

“There rests saint Rumwold in the place that is called Buckingham, near the river Ouse“

Rumwold’s bones remained at Buckingham until the 16th century. He also had an altar dedicated to him at King’s Sutton (his birthplace), which was an important ecclesiastical centre in Anglo-Saxon times and also a royal vill.

The Vita ends:

“There and in many places, when invoked, St Rumwold bestows favours upon those who ask, giving sight to the blind, making the lame to walk, and granting deliverance to the sick weighed down by various ailments, with the consent of our Lord Jesus Christ Who, in the unity of the Trinity in the Trinity of unity, lives and is glorified as God, one with the omnipotent Father and the Holy Spirit, throughout infinite ages, AMEN.”

The 17th century antiquary, Thomas Fuller, who researched the story of Rumwold, said at the end:

“Reader, I partly guess by my own temper, how thine is affected with the reading thereof, whose soul is much divided betwixt several actions at once:

1 To frown at the impudency of the first inventors of …

2 To smile at the simplicity of believers in …

3 To sigh at the well-intended devotion abused by …

… such improbable untruths

4 To thank God we live in times of better and brighter knowledge”

However, following the events of 1066 a number of Vitae were produced due to Norman disbelief in the stories they were told and this would tie in with the date of this Vita. In addition, by stressing the links between the various locations of the story, the Minster may have been trying to protect its income by asserting its spiritual authority. Finally the similarity of Rumwold’s story with that of a young Jesus at the Temple is unlikely to be coincidental. Medieval vitae were less concerned with “fact” and more with spiritual learning, which such stories could promote.

Death of Clarus, 4th November 894

The British priest Clarus was martyred on 4th November 894 AD.

According to a British Martyrology, from 1761:

“On November 4th 894 AD in the territory of Rouen in Normandy, the martyrdom of St. Clarus, a British priest, eminent for sanctity retiring into a wilderness, to avoid the solicitations of an unhappy woman, who was inflamed with an impure love for his person, was murdered by two ruffians, at her suggestion; and so fell a martyr of purity.”

Alban Butler expands a little:

“THIS saint was an Englishman by birth, of very noble extraction, was ordained priest, and leaving his own country led many years an angelical life in the county of Vexin in France. He often preached the truths of salvation to the inhabitants, and died a martyr of chastity, being murdered by two ruffians, employed by an impious and lewd lady of quality, about the year 894. He is named in the Roman and Gallican Martyrologies, and honoured with singular veneration in the diocess of Rouen, Beauvais, and Paris. The village where he suffered martyrdom, situate upon the river Epte (which separates the Norman and French Vexins) nine leagues from Pontoise, and twelve from Rouen, bears his name, and is become a considerable town by the devotion of the people to this saint. His rich shrine is resorted to by crowds of pilgrims, who also visit a hermitage which stands upon the spot which was watered with his blood near the town. Another town in the diocess of Coutances in Normandy, which is said also to have been sanctified by his dwelling there before he retired to the Epte, is called by his name St. Clair.”

Although he was an Englishman based in France, there is a chapel dedicated to him in Exeter in the Livery Dole.

Feast Day of Birstan, 4th November

4th November is the Feast Day of St Byrnstan (Birstan or Brinstan), the Bishop of Winchester from 931-934 AD.

He succeeded Frithestan as Bishop, as Alban Butler tells us:

“He was raised for his eminent sanctity to that see in 931, on the resignation of the pious bishop Frithestan, who died the following year. It was his daily custom to wash the feet of a number of poor whom he served at table; he also every day said mass, and at night repeated the psalms for the faithful departed. He died the 4th of Nov. 934.”

Prior to his elevation to the bishopric, Byrnstan was a mass priest in the household of King Athelstan and was put in place of Frithestan who had been a critic of the king. Frithestan meanwhile lived another year.

Byrnstan may have founded St. John’s Hospital in Winchester but other than a reputation for piety little is known about him beyond the fact that he continued to witness the king’s charters. He died on 1st November, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle although his feast day is 4th November.

His rise in popularity was really due to the promotion of his cult by Athelwold in the 10th century following a vision in which he appeared to his successor and declared:

“I am Birstan, former Bishop of this town” and pointing with his right hand, “This is Birinus, who first preached here,” and with his left, “This is Swithun, particular patron of this church and city”.

Byrnstan was clearly unhappy at his lack of recognition in the city and Athelwold duly reinstated the veneration of the saint as an equal to the other two.

Feast Day of Leonard, 6th November

6th November is the Feast Day of St Leonard of Limoges (or Noblac), a Frankish saint with a slight connection to York.

Leonard was born to noble Frankish parents in the 5th century at the court of King Clovis I (466-511 AD), who also acted as his sponsor at his baptism. He and his brother Liefhard studied at Miscy under Maximus; eventually Liefhard left to establish a monastery while Leonard went to Limoges and settled into a hermit’s life in the nearby forest.

The forest was sometimes used by the king for hunting and during one such hunt the queen, who was staying with the king at the nearby royal residence, went into labour with their child. She had great difficulty with the birth and Leonard was able to ensure the safe delivery of the baby. The king rewarded him by giving him as much of the forest as he could ride around in one night. Kings should really know better where saints are concerned! Leonard was duly grateful and founded a monastery there, called Noblac in recognition of the nobility of the gift. He ruled the community there until his death.

Leonard is the patron saint of prisoners, as he is said to have obtained permission for the release of every prisoner whom he visited whom he judged capable of benefitting from release. It is said that prisoners who invoked him from their cells saw their chains break before their eyes. Many came to him afterwards, and he often gave them land to clear and farm, so that they could live honestly.

He turned down the offer of a bishopric, preferring a more reclusive life.

He died in 559 AD.

A Vita (Life) was written in the early 11th century and his veneration became popular in the 12th century, so his story was really only promoted at the very end of the Anglo-Saxon period.

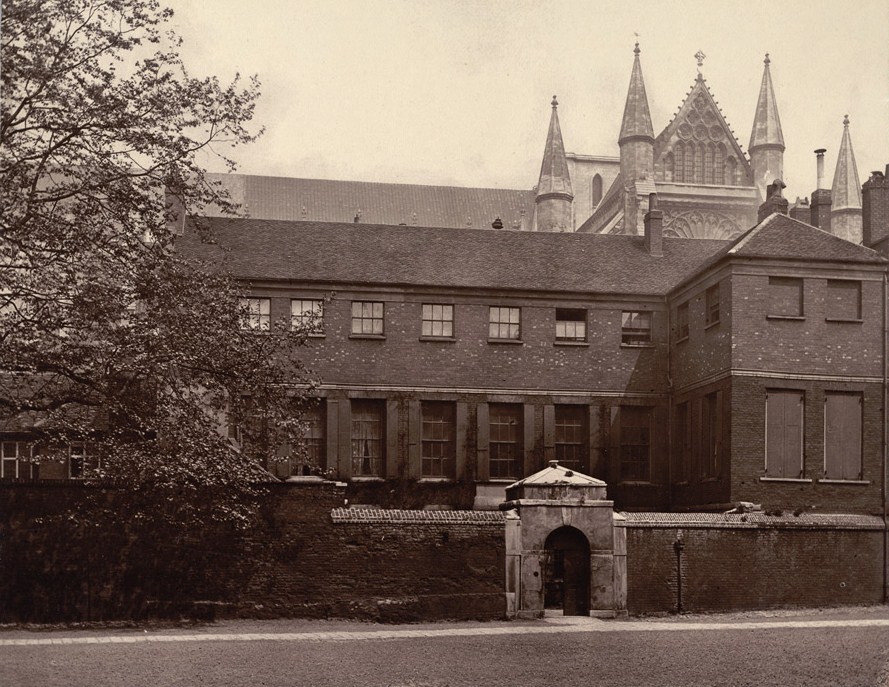

He is associated with York through the 12th century hospital dedicated to him in the city. This was an Augustinian foundation and the ruins can still be seen today in Museum Gardens. It was one of the largest and richest hospitals in England caring for the poor, the sick, orphans and the old. It cared for over 200 people at a time providing food, clothes, medicine and spiritual care.

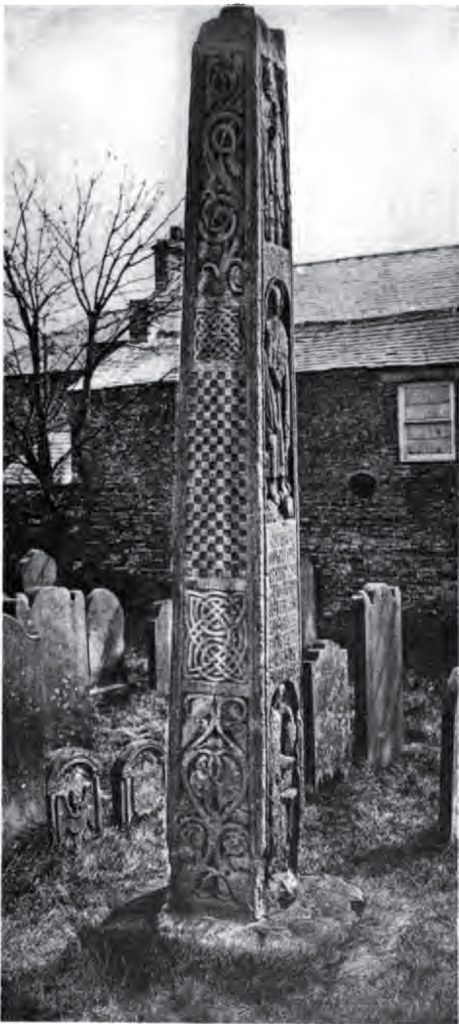

Death of Willibrord, 7th November 739

7th November is the Feast Day of Willibrord, who was a saint and evangelist.

He was born around 658 AD in Northumberland and sent to the monastery in Ripon under Wilfrid at the age of seven, a not uncommon practice for those boys destined for the church.

When he was 20 he went to Ireland to study at Rath Melsigi, which was a renowned centre of learning, and in 690 AD Abbot Ecgberht approved him to lead a mission to convert the Frisians. Another priest, Wigbert, had previously gone to Frisia but had to return to Ireland after a couple of years having failed to convince the population of the benefits of Christianity. Willibrord therefore set out with Swidbert and ten other English monks on his mission.

The Anglo-Saxon drive to convert other people was based in part on the genuine desire to save souls from damnation, as they understood it. However, they were particularly concerned to convert the Frisians because they saw them as among their ancestral kin.

Willibrord was consecrated by the Pope as archbishop of the Frisians in 695 AD and was based at Utrecht. However it was a difficult time in that part of Europe as the Frisians were fighting the Franks under Charlemagne. Willibrord had to retreat to Echternacht (now in Luxembourg) on more than one occasion. He was given land there by Abbess Irmina who was the mother-in-law of King Pepin II (of Herstal), after he helped save her nunnery from plague by blessing the water and saying mass in the church. Between 704-706 AD he built a larger monastery there which included a scriptorium. This became the production site of the Echternacht Gospels, and was one of the most important scriptoria in Frankia.

The life of the missionary in Frisia was fraught with danger. For example, Bede relates the story of two missionaries, both called Hewald, were killed by the Frisians.

King Pepin died in 714 AD and in 716 AD Radbod, king of the Frisians and still a pagan, drove Willibrord and his companions out of Frisia.

Alban Butler tells us of an event during Radbod’s reign:

“In his return [Willbrord returning from Denmark where he had also been preaching] he was driven by stress of weather upon the famous pagan island, called Fositeland, now Amelandt, on the coast of Friesland, six leagues from Leuwarden, to the north, a place then esteemed by the Danes and Frisons as most sacred in honour of the idol Fosite. It was looked upon as an unpardonable sacrilege, for any one to kill any living creature in that island, to eat of any thing that grew in it, or to draw water out of a spring there without observing the strictest silence. St. Willibrord, to undeceive the inhabitants, killed some of the beasts for his companions to eat, and baptized three persons in the fountain, pronouncing the words aloud. The idolaters expected to see them run mad or drop down dead: and seeing no such judgment befal them, could not determine whether this was to be attributed to the patience of their god, or to his want of power. They informed Radbod, who, transported with rage, ordered lots to be cast three times a day, for three days together, and the fate of the delinquents to be determined by them. God so directed it that the lot never fell upon Willibrord; but one of his company was sacrificed to the superstition of the people, and died a martyr for Jesus Christ.”

Willibrord was only able to return following Radbod’s death in 719 AD, supported by Charles Martel, who was Pepin’s son and successor. This was the period when Boniface also worked alongside him for three years before moving on to preach in Germania.

Alcuin wrote about Willibrord and a number of his miracles. He also described him as follows:

“Now this holy man was distinguished by every kind of natural quality: he was of middle height, dignified mien, comely of face, cheerful in spirit, wise in counsel, pleasing in speech, grave in character and energetic in everything he undertook for God.”

Willibrord died on 7th November 739 AD, at the age of 81, before the mission could be said to have fully succeeded; that was left to Boniface who took a more aggressive approach to conversion with the support of Charles Martel. Alcuin describes Willibrord’s funeral, which had a hitch, resolved by another miracle:

“His venerable body was laid to rest in a marble sarcophagus, which at first was found to be six inches too short to hold the entire body of God’s servant. The brethren were greatly concerned at this, and, being at a loss to know what to do, they discussed the matter again and again, wondering where they could find a suitable restingplace for his sacred remains. Wonderful to relate, however, through the lovingkindness of God the sarcophagus was suddenly discovered to be as much longer than the holy man’s body as previously it had been shorter. Therein they laid the remains of the man of God, and to the accompaniment of hymns and psalms and every token of respect it was interred in the church of the monastery which he had built and dedicated in honour of the Blessed Trinity. A sweet and marvellous fragrance filled the air, so that all were conscious that the ministry of angels had been present at the last rites of the holy man.”

Further miracles of healing were then recorded at his tomb, along with a never-empty flagon of wine.

Discovery of the Trewhiddle Hoard, 8th November 1774

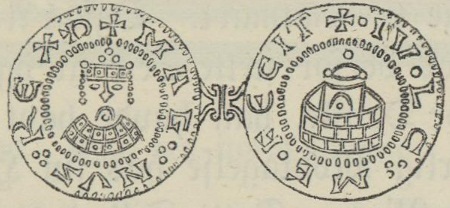

On 8th November 1774 some Cornish tin miners at Trewhiddle made an important discovery. They uncovered a large number of Anglo-Saxon coins, a silver chalice and other precious objects. The coins were of Mercian and Wessex origin and dated the find to around 868-878 AD. This date is significant in that it represents the period of the Viking incursions, around the time Alfred came to the throne following the death of his brother Athelred in 871 AD after the Battle of Merton. It is therefore supposed that the hoard was buried to protect it from the Vikings.

The items were described in some detail by Jonathan Rashleigh, in “The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society” in 1868. He was the great-nephew of Philip Rashleigh, the local squire and Fellow of the Royal Society who first collected them from the miners and published an account in 1778. Of the coins, 114 were retrieved from the workmen but some were dispersed later. The other items included:

“The ornaments consisted of two gold objects (since lost), one of them having been a circular pendent ornament, enriched with filagree; a silver chalice-shaped cup, broken into several pieces, the hollow of the bowl having suffered much from oxidation; a silver cord (considered to have been a “disciplinarium”) of curious twisted workmanship, terminating in four nobbed lashes, like a scourge, at one end, whilst the other end is looped and rove through a dark mottled amulet of glass; a penannular brooch; the tip of a belt; buckles; richly chased bands, supposed to have been bracelets; a long curved pin, the head of which is curiously fashioned with fourteen facets chased in various ornamental patterns, and partly nielloed. Of the above ornaments, all of which are of a rare period, articles are conspicuous, viz,, the silver cup and the silver “disciplinarium”.”

The find gave rise to the identification of a “style” known as Trewhiddle. It is characterised by small fields, or cartouches, usually with beaded frames, containing lively animals, foliage and geometric designs. The background is often inlaid with niello. The designs are usually found on silver items which contrast sharply with the black niello inlay. It was a very popular style and can be found from Cornwall to Northumbria after the 820s. Other examples come from Pentney in Norfolk on disc brooches.

It seems to have been derived from a Mercian animal style but was popular especially with Wessex royalty, of which the finger rings of King Athelwulf and his daughter Athelswith are well known examples. These rings were probably given to their retainers as badges of the household, rather than being worn by the named royals. They also show links to Carolingian designs dating to the time of Charlemagne depicting peacocks drinking from the Fountain of Life. Further examples of the style have been found on the Continent, such as a ring at Bologna, indicating the regularity of journeys to and from Rome and beyond, on pilgrimage or for trade.

In his article Jonathan Rashleigh also included a list of the coins and his conclusion on the dating of the hoard.

“The following is a list of the kings, with the number their coins found at Trewhiddle: –

A.D. 757-796. Offa of Mercia (1)

796 – 818. Coenvulf, ditto (2)

820 – 824. Beornvulf, ditto (1)

839-852. Berhtulf, ditto (10)

852 – 874. Burgred, ditto (45)

874 Ciolvulf, ditto (1)

808 – 840. Eanred of Northumberland – silver penny (unique) (1)

830 – 870. Ceolnoth, Archbishop (6)

800 – 837. Ecgbeorht, sole monarch (3)

887-857. Ethelvulf, ditto (10)

867 – 872. Ethelred, ditto (2)

872-901. Alfred, ditto (2)

814 – 840. Louis le Debonaire of France (1)

Other Saxon pennies never described, about 29

Total 114

Thus, the latest commencement of a reign, amongst these kings, is that of Ciolvulf, AD 874; so that the coins must have been secreted after that date. But as there are but two coins of Alfred, who commenced his reign in AD 872, and who reigned until a later period than any of the other kings whose coins were found at Trewhiddle, it is probable that the treasure was buried about AD 876-7, or early in King Alfred’s reign.”

He then compared them to the coins from other hoards, including Cuerdale and York, as evidence of the spread of a centralised currency issued by “sole monarchs”.

Feast Day of Justus, Archbishop of Canterbury, 10th November

Justus, the fourth Archbishop of Canterbury, died on 10th November around 627 AD.

He had been sent to Britain by the Pope, Gregory the Great, in 601 AD to support Augustine’s earlier mission which had finally arrived in 597 AD. He became the first Bishop of Rochester in 604 AD, being consecrated by Augustine, and was present at the Council of Paris in 614 AD.

However, after the deaths of the Christian kings Athelberht of Kent and Saebert of Essex, both in 616 AD, there was a pagan resurgence led by their sons. Justus fled to Frankia with Bishop Mellitus until it was safe to return. The three sons of Saebert were duly killed in battle against the Gewisse (West Saxons). Athelberht’s son, Eadbald, was converted by Laurence, the Archbishop who remained in Canterbury. Laurence then recalled Justus and Mellitus from Frankia, a year after they had fled.

Justus was able to return to Rochester but Mellitus was less fortunate and was not welcomed back to his See at London. King Eadbald was not strong enough to enforce his return.

Justus became Archbishop of Canterbury in 624 AD and served until his death. He was the Archbishop who consecrated Paulinus in 625 AD before he went to Deira (Yorkshire) with the princess Athelburh who was to marry Edwin. Bede tells us:

“Hereupon the virgin [Athelburh] was promised, and sent to Edwin, and pursuant to what had been agreed on, Paulinus, a man beloved of God, was ordained bishop, to go with her, and by daily exhortations, and celebrating the heavenly mysteries, to confirm her and her company, lest they should be corrupted by the company of the pagans. Paulinus was ordained bishop by the Archbishop Justus, on the 21st day of July, in the year of our Lord 625, and so he came to King Edwin with the aforesaid virgin as a companion of their union in the flesh.”

When Justus died, Paulinus as Bishop of York was able to consecrate his successor Honorius, which he did at Lincoln, according to Bede, although technically this was not proper ecclesiastical procedure.

“IN the meantime, Archbishop Justus was taken up to the heavenly kingdom, on the 10th of November, and Honorius, who was elected to the see in his stead, came to Paulinus to be ordained, and meeting him at Lincoln was there consecrated the fifth prelate of the Church of Canterbury from Augustine. To him also the aforesaid Pope Honorius sent the pall, and a letter, wherein he ordains the same that he had before established in his epistle to King Edwin, viz. that when either of the bishops of Canterbury or of York shall depart this life, the survivor of the same degree shall have power to ordain a priest in the room of him that is departed; that it might not be necessary always to travel to Rome, at so great a distance by sea and land, to ordain an archbishop.”

Edward’s Burh at Hertford, 11th November 912

On 11th November 912 AD Edward the Elder was at the burh (fortification) at Hertford on the southern bank of the River Lea, which he expanded and refortified. The burh had originally been built by his father Alfred in 895 AD, and is now believed to be under the later Norman castle.

This was the time during which Edward and his sister Athelflaed were expanding their father’s original series of burhs to reclaim territory taken by the Scandinavians. Between 910 and 918 AD the brother and sister instigated a campaign of building and aggression against the Scandinavian-led territories (later called the Danelaw).

At this stage Athelflaed had built or strengthened burhs at Bremesburh (probably Bromsberrow near Ledbury), Sceargeat (unknown) and Bridgnorth in the west. Hertford was the first of Edward’s refortifications in the campaign and within months he had added a second burh at Hertford on the north bank of the river. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle year is dated from the September of 912 AD, so Martinmass in November fell in 912 AD (as we would date it) and the later events in 913 AD:

“AD 913. In this year, about Martinmas, king Edward commanded the northern fortress to be built at Hertford, between the Memera, the Benefica, and the Lea. And then after that, during the summer, between Rogation-days [3d May], and midsummer, king Edward went with some of his auxiliaries to Maldon in Essex, and there encamped, whilst the fortress at Witham was wrought and built; and a good part of the people who were before under the dominion of the Danish-men submitted to him: and in the meanwhile some part of his assistants constructed the fortress at Hertford, on the south side of the Lea. This year, by the help of God, Aethelfled, lady of the Mercians, went with all the Mercians to Tamworth, and there built the fortress early in the summer; and after this, before Lammas [1st.], that at Stafford.”

The rivers at Hertford flow to the north and the west of the town. The double fortification at Hertford would have protected London from any forces coming south from the central Danelaw area. At this stage the region of Essex appears to have submitted to Edward, making that border more secure as well.

Edward was able to move on to his next goal by April, but the logistics of the campaign require recognition. He and his sister were able to command and deploy resources to build the fortifications, protect them during the building phase, and garrison the resulting burh before moving on to the next target. This would have also required provisions for the men and animals involved without denuding the surrounding area of food or fodder, as well as providing space for accommodating the body of men and preventing crippling outbreaks of disease from medium to long-term encampments.

After Hertford Edward moved on to Witham; then in 914 AD to Buckingham; in 915 AD Bedford; in 916 AD to Maldon; in 917 AD to Towcester, Wigingamere (possibly Leighton Buzzard), Tempsford, Towcester, Huntindon and Colchester; and then in 918 AD, the year in which Athelflaed died, Stamford and Nottingham (north bank); in 919 AD at Thelwall and Manchester; in 920 AD Nottingham (south bank) and Bakewell; finally in 921 AD Cledemutha (probably Rhuddlan).

While 913 AD saw the submission of Essex in the Danelaw but there was a reaction from elsewhere as the leaders of the Danelaw realised the English were building up for an assault:

“After Easter [17th April], a pagan army from Northampton and Leogereceastre [Leicester], went plundering in the province of Oxford, and slew very many people in the king’s vill of Hokenertune, and in many other vills. Shortly after that one returned home, they equipped another composed of cavalry, and sent it towards Ligetun [Leighton ?] in the province of Hertford. But the natives assembled in force to resist them, and after slaying many of them and putting the rest to flight, captured some horses and the greater part of their arms, and re-captured the booty which they had taken. Leaving a portion of the army to build a city on the south side of the river Lige [Lea], king Eadward marched, after the rogations [23d May], with the greater part of it into East Saxony, and encamped at Mealdune: he remained there until a city was built at Witham and fortified ; and a great number of the people there, who were in subjection to the pagans, submitted themselves and all their property to him.”

Edward is less well-known than his father and often overshadowed by his son, Athelstan, whose success at Brunanburh in 937 AD is quoted as the time when England was united (although of course he was never actually crowned as King of England – that honour went first to Edgar). Nevertheless earlier chroniclers recognised his achievements in setting the stage for what followed.

William of Malmesbury says that:

“he [Edward] was much inferior to his father in literature, but greatly excelled in extent of power. For Alfred, indeed, united the two kingdoms of the Mercian and West Saxons, holding that of the Mercians only nominally, as he had assigned it to prince Ethelred: but at his death Edward first brought the Mercians altogether under his power, next, the West and East Angles, and Northumbrians, who had become one nation with the Danes; the Scots, who inhabit the northern part of the island; and all the Britons, whom we call Welsh, after perpetual battles, in which he was always successful. He devised a mode of frustrating the incursions of the Danes; for he repaired many ancient cities, or built new ones, in places calculated for his purpose, and filled them with a military force, to protect the inhabitants and repel the enemy. Nor was his design unsuccessful; for the inhabitants became so extremely valorous in these contests, that if they heard of an enemy approaching, they rushed out to give them battle, even without consulting the king or his generals, and constantly surpassed them, both in number and in warlike skill. Thus the enemy became an object of contempt to the soldiery and of derision to the king.”

Edward has no statues or popular stories, but he did the hard work needed to help his successors take control of what later became England. It is unlikely he had a vision of England as we would understand it, but nevertheless he contributed to its eventual emergence.

Death of King Cnut, 12th November 1035

On 12th November 1035 King Cnut died at Shaftesbury and was buried at Winchester Old Minster. He was succeeded in England by his son Harold Harefoot, while his other son, Harthacnut, took and fought to hold the throne of Denmark.

According to the Knytlinga Saga:

“Knut was exceptionally tall and strong, and the handsomest of men, all except for his nose, that was thin, high-set, and rather hooked. He had a fair complexion none-the-less, and a fine, thick head of hair. His eyes were better than those of other men, both the handsomer and the keener of their sight.”

Cnut was the son of Sweyn Forkbeard, the Dane who was briefly King of England (by right of conquest), having finally driven out Athelred Unrede in 1013 after extorting tribute from him for a number of years. However, Sweyn did not live long to enjoy the fruits of his victory and died in February 1014.

On Sweyn’s death the Danelaw came out in support of Cnut but the other English nobles recalled Athelred from Normandy where he was in exile. Athelred returned to England, and, in a pre-cursor to the events of Runnymede in 1215 when King John Lackland signed the Magna Carta, Athelred swore to be a better king and rule more justly. Cnut at this time was a young warrior, relatively untried as a leader of men, and despite his support in parts of the country he was driven out by the English until he returned in full force in 1015. He was much more effective in this later campaign and took most of the country, with the only meaningful resistance being brought by Edmund Ironside, son of Athelred.

After Athelred’s death in 1016 Edmund fought back even more vigorously against Cnut so that by November the two were brought to an agreement at Deerhurst to split the country between them. However, Edmund died soon after, possibly as a result of wounds but it is not known, and Cnut became sole ruler of England with his coronation taking place on Christmas Day. In 1017 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us:

“AD 1017. In this year king Cnut obtained the whole realm of the English race, and divided it into four parts: Wessex to himself, and East Anglia to Thurkyll, and Mercia to Eadric, and Northumbria to Irke. And in this year was Eadric the ealdorman slain in London, very justly, and Northman, son of Leofwine the ealdorman, and Aethelweard, son of Aethelmaer the great, and Brihtric, son of Aelfeh, in Devonshire. And king Cnut banished Eadwigthe etheling, and afterwards commanded him to be slain, and Eadwi, king of the churls. And then, before the kalends of August, the king commanded the relict of king Aethelred, Richard’s daughter, to be fetched for his wife, ‘that was Elfgive in English, Ymma in French.”

His wife, Emma of Normandy, was daughter of Richard of Normandy, widow of King Athelred Unrede and mother of Edward and Alfred. She and Cnut had two children of their own, Gunnhilda and Harthacnut. Cnut also had a “Danish” wife, Alfgifu of Northampton, with whom he had a son known as Harold Harefoot.

Cnut ruled from 1016-1035. He established the earldoms of England and although he initially controlled Wessex directly he eventually created the Earldom of Wessex which was given to Godwin, establishing that family’s rise to power. Cnut’s brother Harold was King of Denmark, and when he died in 1018 Cnut took the throne of Denmark as well as England. In Norway, Olaf had replaced Sweyn Forkbeard as king but in 1029 his nobles supported the invasion of Cnut and so Cnut became King of Norway as well.

England took up Cnut’s main attention and he placed Alfgifu and their son Harold as regents in Norway with disastrous consequences. Their rule was so unpopular that they were driven out by Magnus, the son of Olaf, in 1035; Magnus was only an eleven year old boy but he was proclaimed king by the Norwegian nobles in preference to Alfgifu and Harold.

Cnut worked with the church, particularly Bishop Wulfstan, to rule England according to English laws and customs from the time of King Edgar. He promoted men he trusted from the English ranks as well as Danish. In 1027 he was able to leave the kingdom securely while he travelled to Rome to witness the coronation of Conrad, the Holy Roman Emperor. While in Rome he negotiated fiercely for better terms for English merchants, pilgrims and churchmen. He wrote in a letter to his nobles:

“I spoke with the Emperor himself and the Lord Pope and the princes there about the needs of all people of my entire realm, both English and Danes, that a juster law and securer peace might be granted to them on the road to Rome and that they should not be straitened by so many barriers along the road, and harassed by unjust tolls; and the Emperor agreed and likewise King Robert who governs most of these same toll gates. And all the magnates confirmed by edict that my people, both merchants, and the others who travel to make their devotions, might go to Rome and return without being afflicted by barriers and toll collectors, in firm peace and secure in a just law.”

Henry of Huntingdon, writing in the 12th century, records a summary of his reign including the curious story of the King Cnut and the Tide:

“A few words must be devoted to the power of this king. Before him there had never been in England a king of such great authority, He was lord of all Denmark, of all England, of all Norway, and also of Scotland. In addition to the many wars in which he was most particularly illustrious, he performed three fine and magnificent deeds. The first is that he gave his daughter in marriage to the Roman emperor, with indescribably riches. The second, that on his journey to Rome, he had the evil taxes that were levied on the road that goes through France, called tolls or passage tax, reduced by half at his own expense. The third, that when he was at the height of his ascendancy, he ordered his chair to be placed on the sea-shore as the tide was coming in. The he said to the rising tide, “You are subject to me, as the land on which I am sitting is mine, and no one has resisted my overlordship with impunity. I command you, therefore, not to rise onto my land, nor to presume to wet the clothing or limbs of your master.” But the sea came up as usual, and disrespectfully drenched the king’s feet and shins. So jumping back, the king cried, “Let all the world know that the power of kings is empty and worthless, and there is no king worthy of the name save Him by whose will heaven, earth and sea obey eternal laws.” Thereafter King Cnut never wore the golden crown, but placed it on the image of the crucified Lord, in eternal praise of God the great king. By whose mercy may the soul of King Cnut enjoy rest.”

Cnut was buried at the Old Minster in Winchester, which he and Queen Emma had richly endowed, and his bones were translated to a mortuary chest when the cathedral was rebuilt. In the English Civil War (17th century) his bones were scattered and trampled with others by soldiers, and only later collected and placed back in the mortuary chests, although in a muddled fashion with the other victims of the desecration.

Wasting of Worcester, 12th November 1041

On 12th November 1041 King Harthacnut laid waste to Worcester after the murder of his tax collectors on 4th May in that city. They had been killed when attempting to collect the hated heregeld or tax that Harthacnut imposed on coming to the throne.

John of Worcester records the year in detail:

“AD 1041: This year Hardicanute, king of England, sent his huscarls through all the provinces of his kingdom to collect the tribute which he had imposed. Two of them, Feader and Thurstan, were slain on the 4th of the ides [the 4th] of May, by the citizens of Worcester and the people of that neighbourhood, in an upper chamber of the abbey-tower, where they had concealed themselves during a tumult. This so incensed the king, that to avenge their deaths he sent Thorold, earl of Middlesex, Leofric, earl of Mercia, Godwin, earl of Wessex, Siward, earl of Northumbria, Roni, earl of Hereford, and all the other English earls, with almost all his huscarls, and a large body of troops, to Worcester, where Alfric was still bishop, with orders to put to death all the inhabitants they could find, to plunder and burn the city, and lay waste the whole province. They arrived there on the second of the ides [the 12th] of November, and beginning their work of destruction through the city and province continued it for four days ; but very few of the citizens or provincials were taken or slain, because, having notice of their coming, the people fled in all directions. A great number of the citizens took refuge in a small island, called Beverege, situated in the middle of the river Severn, and having fortified it, defended themselves so stoutly against their enemies that they obtained terms of peace, and were allowed free liberty to return home. On the fifth day, the city having been burnt, every one marched off loaded with plunder, and the king’s wrath was satisfied. Soon afterwards, Edward, son of Ethelred the late king of England, came over from Normandy, where he had been an exile many years, and being honourably received by his brother, king Hardicanute, remained at his court.”

Leofric of Mercia, one of the earls sent to Worcester, would have had some concerns. He had supported Harthacnut’s brother Harold Harefoot previously, although he had remained in his seat following Harold’s death. In addition Worcester was the cathedral city of his people and so presumably close to his heart. It had been fortified in Alfred’s burh-building programme under Bishop Waerfrith and became a centre of church learning and influence. Oswald of Worcester had been a key figure in the Church reform movement in the later 10th century along with Athelwold and Dunstan. However, in 1041 the Bishop was Alfric Puttoc (Hawk), a supporter of King Harthacnut, and in fact one of the men who was instructed by him to find King Harold Harefoot’s body, disinter it and throw it in the sewer. In 1040 Alfric had also been the accuser of Earl Godwin and Bishop Lyfing, the then Bishop of Worcester, in the murder of Alfred Atheling; as a result Lyfing lost his Bishopric and Alfric took over. Lyfing however made his peace with Harthacnut and was reinstated in 1041 after the ravaging of the city.

Leofric was a man who gave a great deal of money to the church and Worcester was among the recipients.

Harthacnut died the following year at a wedding feast and Edward the Confessor took the throne.

St Brice’s Day Massacre, 13th November 1002

The St Brice’s Day Massacre took place on 13th November 1002.

Earlier in the year King Athelred had made a truce with the Danes by agreeing a payment of tribute of 24,000 lbs of silver. It was also the year in which he married Emma of Normandy and translated the bones of Oswald, Archbishop of York to a new shrine. He had to appoint a new archbishop later in the year. Then, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1002:

“Moreover, in this year king Athelred ordered all the Danes who were in England, both great and small, of either sex, to be slain, inasmuch as they had endeavoured to deprive him and his nobles of their lives and kingdom, and to get possession of the whole realm of England.”

Henry of Huntingdon, writing in the 12th century, expanded on the Chronicle’s account:

“In the year 1002, Emma, the jewel of the Normans, came to England and received the crown and title of queen. With her arrival, King Athelred’s pride increased and his faithlessness grew: in a treacherous plot, he ordered all the Danes who were living peacefully in England to be put to death on the same day, namely the Feast of St Brice. Concerning this crime, in my childhood [Henry was born c.1088] I heard very old men say that the king had sent secret letters to every city, according to which the English either maimed all the unsuspecting Danes on the same day and hour with their swords, or, suddenly, at the same moment, captured them and destroyed them by fire.”

It is possible the Danes were in fact the remnants of the troops who had been paid off by the silver, but it is not clear. Similarly a story grew up, reported by William of Malmesbury, that Sweyn Forkbeard’s sister died in the massacre; however William’s account is so muddled it needs to be treated very cautiously as he ascribes her death to 1013 with the massacre following the murder of Archbishop Alfheah. It is however possible she was killed in 1002 as Sweyn did also invade in 1003 which would fit the chronology, but it is by no means certain.

There has been some debate as to whether or how the order was carried out; it would seem unlikely to have been followed in the former Danelaw region of England where many inhabitants had Danish heritage and there was no meaningful distinction between “English” and “Dane”. However, it seems that St Frideswide’s Church in Oxford, on the borders of the Danelaw, was burned to the ground when people took refuge inside. According to a charter of St Frideswide dating from 1004 AD Athelred refers to the incident when he grants the monastery a new title-deed:

“In the year of the incarnation of our Lord 1004, the second indiction, in the 25th year of my reign, by the ordering of God’s providence, I, Aethelred, governing the monarchy of all Albion, have made secure with a liberty of privilege by royal authority a certain monastery situated in the town which is called Oxford, where the body of the blessed Frideswide rests. And I have restored the territories which belong to that monastery of Christ with the renewal of a new title-deed; and I will relate in a few words to all who look upon this document for what reason it was done.

For it is fully agreed that to all those dwelling in this country it will be well known that, since a decree was sent out by me with the counsel of my leading men and magnates, to the effect that all the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockles amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination, and this decree was to be put into effect even as far as death; so those Danes who dwelt in the aforementioned town, striving to escape death, entered the sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and bolts, and resolved to make a refuge and defence for themselves there in against the people of the town and the suburbs. But when all the people in pursuit strove, forced by necessity, to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to the planks and burned, as it seems, this church with its ornaments and its books. Afterwards, with God’s aid, it was renewed by me and my subjects, and, as I have said above, it was strengthened in Christ’s name with the honour of a fresh privilege, along with the territories belonging to it, and endowed with every liberty, regarding royal exactions as well as ecclesiastical dues.”

The term “cockles amongst the wheat” is taken from a parable in the Bible in which a field of good seed is infested with cockles, or weeds, planted by an enemy. They are left to grow until harvest when the mature plants are easier to separate from the wheat and can be burned. In medieval times this was interpreted as a warning against sin which needed to be expunged.

Archaeology confirms that a community of Danes was living in the town and it is possible they had been singled out in the wake of the king’s order. Whether they were mercenaries who had settled, or traders, or simply a more identifiably Danish community is unknown.

In the records it is clear the decision was not randomly taken by the king, but made with the agreement of his advising council. This would have included well-known figures such as Alfric of Canterbury, Wulfstan of York, Athelmaer and Queen Emma, who attested a number of charters and decisions at this time.

Two archaeological discoveries have been tentatively linked to the massacre. In 2008, at Oxford, a mass grave at St John’s College was found. The skeletons were all male, mostly aged 16-25 and dumped in a ditch outside the town boundaries. All showed signs of injury at the time of death, most commonly blade wounds to the back which would fit an explanation in which they were attempting escape. Several had been burned. There were virtually no personal items among them, indicating they had been stripped. Dating is inconclusive and may have been earlier than 1002, but it is possible they do in fact date to this event

In 2009 a mass burial in Dorset contained men aged in their teens to twenties of whom at least 31 had come from Scandinavia and lived there until shortly before their death. They display trauma around the head and neck and there are no defensive wounds so they were probably executed. The dates for these skeletons are more securely in the period 980-1020 although Dorset saw a number of attacks in this period and the bodies may have been from a different incident in which a raiding party was captured and killed. However, the lack of other wounds implies they had not fought in self-defence beforehand leading to the possibility they were in fact caught unprepared in 1002.

Whether the skeletons were men killed in 1002 or in other related incidents of the years of Viking invasions we are reminded that such executions did occur.

However, the policy proved disastrous. In 1003 Sweyn Forkbeard descended on England and devastated the eastern coast.

Death of Emperor Justinian, 14th November 565

The Emperor Justinian I “the Great” died on 14th November 565 AD. He was Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire and immensely influential throughout Europe.

Firstly he was determined to reunite the two halves of the Roman Empire and promulgated a number of military campaigns and wars to achieve this as well as to expand Roman influence. Under his rule, General Belisarius defeated the Vandals in North Africa, then with his colleague General Narses and others he took Rome and much of Italy back from the Ostrogoths. Roman control of the Western Mediterranean was restored and with it, the vast income and wealth from an expanded Roman hegemony.

Justinian also oversaw the extension of Roman influence to the east where previously it had not reached, and engaged the Sassanid Empire.

He also rewrote the legal code, known as the “Corpus juris civilis” (Body of Civil Law) or the “Code of Justinian”. These influenced the canon law of the church in Rome and arguably the whole western legal tradition up to the present day. Much of it was draconian by modern standards and aimed at protecting the Christian church and outlawing paganism. However, in other areas it also established, for example, the distinction between “law” and “custom”.

Justinian was also a builder (or at least, he paid for buildings to be constructed). These include treasures such as the rebuilt Hagia Sophia and the completion of San Vitale in Ravenna, as well as underground cisterns to protect the water supply to Constantinople, a dam at Dara to prevent floods, and the Sangarius Bridge to secure military supply trains.

His reign also saw the flourishing of poets and historians such as Procopius and the establishment of centres of learning. He developed trade and made government administration more efficient as well as combating corruption.

His reign was marked by natural disasters: the Beirut earthquake, extreme weather conditions and perhaps most notably, plague. The latter became known as the Justinian Plague and spread across Europe over the 6th century killing millions at a time when people had been weakened by famine from the extreme weather events of 535-536 AD which may have been caused by volcanic eruptions in the tropics. It is the first documented outbreak of Bubonic Plague, reported by Procopius in 541 AD. As it spread it impacted the outcomes of wars and potentially was affected the British kingdoms at the time of the Anglo-Saxon arrivals, although this is more speculation than historic fact based on a reference in British sources to the “Yellow Plague of Rhos” around 547 AD. The plague continued to have sporadic outbreaks through the next 200-300 years but nothing so overwhelming was seen again until the Black Death in the 14th century.

Much of what we know about Justinian, and also his wife the Empress Theodora, was written by Procopius. However, even here there is doubt and ambiguity, more than simply caused by the usual distance between us in time and cultural perspectives. His “Wars” describe the military campaigns led by Belisarius; then the “Buildings” is a praise document to the emperor about his public building works. However, at the same time as this he wrote the “Secret History”, which is a bitter and disillusioned story about the corruption and immorality of the emperor, the empress, Belisarius and his wife.

Battle of Winwaed, 15th November 655

On 15th November 655 AD King Oswiu of Northumbria faced the army of Penda which outnumbered him 3:1. Penda of Mercia had killed King Edwin of Northumbria at Hatfield Chase in 633 AD and Oswiu’s brother King Oswald at Maserfield in 642 AD. Penda had had unrivalled military success for years, but Oswiu faced Penda’s opposing forces resolutely. The battle is known as the Battle of Winwaed.

The situation was complicated by the shifting allegiances of other key figures. Bede explains it as follows:

“he [Oswiu] gave battle with a very small army against superior forces: indeed, it is reported that the pagans had three times the number of men; for they had thirty legions, led on by most noted commanders. King Oswy and his son Alfrid met them with a very small army, as has been said, but confiding in the conduct of Christ; his other son, Egfrid, was then kept as hostage at the court of Queen Cynwise, in the province of the Mercians. King Oswald’s son Ethelwald, who ought to have assisted them, was on the enemy’s side, and led them on to fight against his country and uncle; though, during the battle, he withdrew, and awaited the event in a place of safety. The engagement beginning, the pagans were defeated, the thirty commanders, and those who had come to his assistance were put to flight, and almost all of them slain; among whom was Ethelhere, brother and successor to Anna, king of the East Angles, who had been the occasion of the war, and who was now killed, with all his soldiers. The battle was fought near the river Vinwed, which then, with the great rains, had not only filled its channel, but overflowed its banks, so that many more were drowned in the flight than destroyed by the sword.”

The battle site is a matter for passionate debate but it is generally agreed that it was somewhere in the vicinity of Leeds in West Yorkshire. There is contradictory evidence that Oswiu had agreed tribute to Penda in return for peace; in one chronicle Penda accepted and shared out the treasure, and in another he rejected the offer. There is also a reference to Ecgfrith, Oswiu’s son, being a hostage; however that may have been part of a deal agreed in which hostages were provided.

The combined Northumbrian kingdom had split back into its constituent two kingdoms following Oswald’s death. Bede reported Œthelwald’s decision to stay out of the battle; he was the son of Oswald (so Oswiu’s nephew) and King of Deira at this time, and Oswiu, Oswald’s brother, was King of Bernicia. It is not clear whether the two men agreed to the split or were in opposition to one another, although Œthelwald’s alliance with Penda appears to indicate conflict. After the battle Oswiu installed his own son Alhfrith as King of Deira, although they also clashed, especially at the Synod of Whitby.

Penda was let down by another ally in the battle, Cadafael ap Cynfeddw of Gwynedd who had succeeded Cadwallon in 634 AD. He was later known, according to Nennius, as Cadafael Cadomedd, or “Battle-Seizer Battle-Shirker” because of his perceived cowardice.

Athelhere, son of Eni, was also the nephew of Raedwald of East Anglia. His brother (or possibly cousin) Ecgric had been killed by Penda when he had been King in around 636 AD. His second brother Anna then became king and was killed, again fighting Penda. The presence of Athelhere in Penda’s army suggests that he was Penda’s client king. Henry of Huntingdon tells us that:

“In this engagement the pagans were defeated and all the 30 commanders [with Penda] were slain; for the God of Battles was with his faithful people and broke the might of King Penda, and unnerved the boasted strength of his arm, and caused his proud heart to fail, so that his assaults were not as they were wont to be, and the arms of his enemies prevailed against them. He was struck with amazement at finding that his foes were now become to him what he had formerly been to them, and that he was to them what they had been to him. He who had shed the blood of others now suffered what he had inflicted on them, while the earth was watered with his blood, and the ground was sprinkled with his brains.”

Penda is known as the last pagan king of the Anglo-Saxons, and his death is often seen as the end of the pagan age in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. However, the purpose of the battle was not religious, it was political. It was about power and control of kingdoms and people as can be seen by the mixture of loyalties within and between the armies.

Queen Emma loses her jewels, 16th November 1042

On 16th November 1042 Queen Emma’s son Edward (the Confessor) and his earls descended upon her at Winchester and took all of her gold, jewellery and precious things allegedly because of the way she had treated Edward as a boy. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us about the new king’s decision:

“AD 1043. This year was Edward consecrated king at Winchester on the first day of Easter [3d April]. And this year, fourteen days before Andrews-mass [16th Nov.], the king was advised to ride from Gloucester, and Leofric the earl, and Godwine the earl, and Sigwarth [Siward] the earl, with their followers, to Winchester, unawares upon the lady [Emma]; and they bereaved her of all the treasures which she possessed, they were not to be told, because before that she had been very hard with the king her son; inasmuch as she had done less for him than he would, before he was king, and also since: and they suffered her after that to remain therein.”

He then deposed Stigand, who had only that year been made Bishop of East Anglia, because of his closeness to Emma and seized all his lands as well. After which he married Earl Godwin’s daughter, Edith.

Meanwhile William of Malmesbury recognised some good in the queen mother:

“his mother had for a long time mocked at the needy state of her son, nor ever assisted him; transferring her hereditary hatred of the father to the child; for she had both loved Canute more when living, and more commended him when dead: besides, accumulating money by every method, she had hoarded it, regardless of the poor, to whom she would give nothing, for fear of diminishing her heap. Wherefore that which had been so unjustly gathered together, was not improperly taken away, that it might be of service to the poor, and replenish the king’s exchequer. Though much credit is to be attached to those who relate these circumstances, yet I find her to have been a religiously-disposed woman, and to have expended her property on ornaments for the church of Winchester, and probably upon others.”

This was also the year in which her son by Cnut, Harthacanut, had died and she had lost not only her wealth but also her power at court. Until this point she had probably been the richest and most powerful woman in England.

Emma died on 6th March 1052.

Death of Queen Margaret of Scotland, 16th November 1042

Margaret of Scotland died on 16th November 1093.

Margaret was born around 1045 in Hungary and was the sister of Edgar the Atheling, the heir apparent to the English throne in 1066, and of Cristina. They had been in England a little over 10 years having returned in 1057 when their father Edward the Exile was invited by Edward the Confessor to return and secure the English succession. Unfortunately her father died of sickness almost immediately upon reaching England but the family remained at the English court and the children grew up with some expectation that Edgar might inherit the throne instead. This view was changed dramatically in 1066 when Edward the Confessor died and Harold Godwinson was chosen as king, Edgar being too young and inexperienced to take the throne at a time when England was under threat from invasion. However, following Harold’s death Edgar was proclaimed king by a number of the nobles although he was never crowned.

Following the coronation of the Norman Duke William, Edgar was taken to Normandy as a hostage and did not return until 1068. At this point the family fled to the Continent but were caught in storms and driven aground in Scotland, traditionally near North Queensferry. Simeon of Durham claims they spent the winter in Scotland but then places them back in York in 1070 after the Harrying of the North, when they once again fled. Meanwhile King Malcolm of Scotland was ravaging Northumbria.

Simeon of Durham tells us how they met:

“When he [Malcolm] was riding along the banks of the river, beholding from an eminence the cruel exploits of his men against the unhappy English, and feasting his mind and eyes with such a spectacle, it was told him that Edgar Atheling and his sisters, who were beautiful girls of the royal blood, and many other very rich persons, fugitives from their homes, lay with their ships in that harbour. When they came to him with terms of amity, he addressed them graciously, and he pledged himself to grant them and all their friends a residence in his kingdom as long as they chose.”

When they returned to Scotland Malcolm and Margaret were married, and she immediately had a positive influence on the rather rough and rowdy king:

“By her care and labour the king himself, laying aside the barbarity of his manners, became more gentle and civilized. Of her he begat six sons, Eadward, Eadmund, king Eadgar, king Alexander, Ethelred, and king David, and two daughters, Matilda queen of the English, and Mary, whom Eustace count of Bologne took in marriage.”

Margaret was very popular in Scotland, renowned for good works and charity, and pious, introducing religious reform to the church to bring it in line with continental practice. As well as establishing a monastery at Dunfermline, restoring Iona Abbey and interceding for English victims of Norman injustice, she set up ferries at Queensferry (hence the name) and North Berwick to ensure pilgrims could cross the Firth of Forth safely on their way to and from St Andrew’s in Fife.

Malcolm undertook several campaigns in support of Edgar’s claim to the throne of England but these were not successful. By 1093 he was attempting to negotiate with William Rufus for peace but not succeeding with that either. On 13th November the English and Scots met at the Battle of Alnwick and Malcolm and their eldest son Edward were killed fighting an army led by Robert de Mowbray.

On hearing the news, Margaret died of a broken heart.

“On hearing of his death, Margaret, queen of Scots, was afflicted with so great distress, that she at once fell into a severe illness; and without delay, summoning her priests, she went into the church, and having confessed her sins to them, she caused herself to be anointed with oil and strengthened by the heavenly viaticum, beseeching God with constant and most earnest prayers, that He would no longer allow her to continue in this miserable life. Nor were her prayers long unheard; for three days after the king’s death, she was freed from the fetters of the flesh, and passed, as we trust, to the joys of eternal salvation. For while she lived she had devoutly cultivated piety, justice, peace and charity. She was frequent in prayers, and kept under her body by watching and fasting; she endowed churches and monasteries; she loved and honoured the servants and handmaids of the Lord; she divided her bread to the hungry; clothed the naked; gave lodging, garments and food to all wanderers who came to her; and she loved God with her whole heart.”

Margaret and Malcolm had eight children, among them Edith (Matilda) who later married Henry I of England, William of Normandy’s son, providing a start towards the unification of the Norman and Anglo-Saxon houses. Three or four of Margaret’s surviving sons became kings of Scotland in turn: Edmund (evidence for his kingship is disputed), Edgar, Alexander and David. Her youngest son, David, honoured her memory by building St. Margaret’s Chapel at Edinburgh Castle on the spot where his mother died.

She was canonised in 1250 and on 19th June 1250, both her body and that of Malcolm were exhumed and removed to a magnificent shrine. Mary, Queen of Scots had St. Margaret’s head removed as a reliquary to Edinburgh Castle in the 16th century and in 1597 it was taken by a “gentleman” to Antwerp, then France when it was lost during the French Revolution.

Death of Abbess Hild, 17th November 680

Abbess Hild died at Whitby on 17th November 680 AD at the age of 66.

Bede tells us that she had spent the first 33 of her years living “most nobly in the secular life” and then spent her remaining 33 years dedicated to God. Bede says:

“she was nobly born, being the daughter of Hereric, nephew to King Edwin, with which king she also embraced the faith and mysteries of Christ, at the preaching of Paulinus, the first bishop of the Northumbrians.”

She was born therefore around 616 AD to Hereric and Bregusuit, and was baptised perhaps at Easter 627 AD with King Edwin and a number of his relatives in York. Hereric was poisoned at the court of King Cerdic (or Ceretic) of Elmet. It is possible he had gone to Cerdic following the annexation of Deira by Athelfrith around 605 AD which saw the death of Aelle, Edwin’s father, and Edwin’s exile; Edwin later deposed Cerdic about 619 AD, possibly in retribution. Hereric’s relationship to Edwin is not known but he may have been a cousin, nephew or even unrecorded brother.

At the age of 33, Hild decided to enter the religious life and went first to East Anglia. Her sister Heresuid was the mother of the king there and had retired to a nunnery in France, and Hild intended to join her. However, after a year in East Anglia she was called by Bishop Aidan to Northumbria where she lived on the north side of the River Wear with a small number of companions.

After a year there she was then sent to a new monastery at Hartlepool (Hereteu), which had been established around 640 AD by Heiu, the first Northumbrian woman to become a nun. Hild took over the rule of the monastery and established a regular system as she had been taught by Aidan and others. King Oswiu entrusted his daughter Alfflaed to Hild’s care during this time. She was recognised for her wisdom and frequently visited by leading churchmen.

In 657 AD she established a foundation at Whitby (Streaneshalch) which she set up on the same principles as Hartlepool.

Bede continues:

“so that, after the example of the primitive church, no person was there rich, and none poor, all being in common to all, and none having any property. Her prudence was so great, that not only indifferent persons, but even kings and princes, as occasion offered, asked and received her advice; she obliged those who were under her direction to attend so much to reading of the Holy Scriptures, and to exercise themselves so much in works of justice, that many might be there found fit for ecclesiastical duties, and to serve at the altar.”

Five bishops were trained under her direction, including Wilfrid.

The Synod of Whitby, held in 664 AD, was convened to discuss a range of important church issues, including the decision to follow either the rule of Rome or the rule of the Irish church, and thus establish the correct way to calculate the date of Easter. Hilda presided over the conference, and was in favour of the Irish rule as was King Oswiu who convened the Synod. However, the final decision went to Rome following passionate argument by Wilfrid, her former protégé.

Another of Hild’s protégés was the poet Caedmon His story describes How he miraculously began to compose poetry on Biblical themes following a vision one night. He repeated his initial composition to Hild and she asked him to make another poem to test that his gift came from a holy source, and upon his successful composition, as Bede describes:

“the abbess, embracing the grace of God in the ‘man, instructed him to quit the secular habit, and take upon him the monastic life; which being accordingly done, she associated him to the rest of the brethren in her monastery, and ordered that he should be taught the whole series of sacred history. Thus Caedmon ‘ keeping in mind all he heard, and as it were chewing the cud, converted the same into most harmonious verse; and sweetly repeating the same, made his masters in their turn his hearers.”

After Hild’s death Eanflaed, King Edwin’s daughter and Oswiu’s widow, became Abbess of Whitby jointly with her own daughter Alfflaed.

A local legend says that when sea birds fly over Whitby Abbey they dip their wings in honour of Saint Hilda. Her symbol, the ammonite, can be seen in a number of locations around the area, such as Ellerburn Church in Dalby, North Yorkshire.

Death of Queen Elfrida, 17th November

17th November around the year 1000 AD saw the death of Elfrida (Alfthryth), the wife of King Edgar and mother of kings Edmund and Athelred.

She was born around the 940s to Ordgar, a wealthy nobleman in Wessex. Her brother Ordulf founded Tavistock Abbey. According to the later chronicler Gaimar, Elfrida was able to get her own way much of the time and was indulged by her father and she probably had a reasonable education and would have been prepared for a suitable marriage to one of the noble families of the period.

Her first husband was Athelwald, son of Athelstan Half-King of East Anglia. However, she was famous for her beauty and King Edgar was famous for having an eye for the ladies. The result was that Athelwald died and Elfrida ended up marrying Edgar. William of Malmesbury likes to tell a legend of considerable intrigue, although limited reliability:

“There was, in his time, one Athelwold, a nobleman of celebrity and one of his confidants. The king had commissioned him to visit Elfthrida, daughter of Ordgar, duke of Devonshire, (whose charms had so fascinated the eyes of some persons that they commended her to the king), and to offer her marriage, if her beauty were really equal to report. Hastening on his embassy, and finding everything consonant to general estimation, he concealed his mission from her parents and procured the damsel for himself. Returning to the king, he told a tale which made for his own purpose; that she was a girl nothing out of the common track of beauty, and by no means worthy such transcendent dignity. When Edgar’s heart was disengaged from this affair, and employed on other amours, some tattlers acquainted him, how completely Athelwold had duped him by his artifices. Paying him in his own coin, that is, returning him deceit for deceit, he showed the earl a fair countenance, and, as in a sportive manner, appointed a day when he would visit his far-famed lady. Terrified, almost to death, with this dreadful pleasantry, he hastened before to his wife, entreating that she would administer to his safety by attiring herself as unbecomingly as possible: then first disclosing the intention of such a proceeding.”

Rather than listen to her husband, Elfrida then so inflamed the king’s passion that he took Athelwald hunting and in the forest ran him through with a spear so he could marry the widow!

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, they married in 964 AD:

“Eadgar, the pacific king of the English, married Alftryth, daughter of Ordgar, ealdorman of Devonshire, after the death of her husband Aethelwold, the glorious ealdonnan of the East Angles; and had by her two sons, Eadmund and Aethelred. He had also previously by Ethelfleda the Fair, surnamed Ened, a son called Eadward, afterwards king and martyr; and by St. Wulfrith a daughter named Eadgith, one of God’s most pious virgins.”

When Edgar had his second coronation in 973 AD Elfrida was crowned alongside him as Queen of England; so not only was Edgar the first king crowned King of England, but she was its first Queen. She had probably also been crowned earlier when they were married as she was particularly keen to emphasise that her sons were the legitimate children of Edgar and made sure they appeared higher in the witness list on charters than his first son Edward.

Elfrida and Edgar were keen church reformers and Elfrida founded Wherwell Abbey where she later retired there until her death.

Her negative reputation comes from the murder of her step-son King Edward (the Martyr) at Corfe Castle when he visited her there in March 978 AD. Her involvement is unclear and much evidence from chronicles can be assigned to misogynist monks, although that does not mean it is untrue.